My blog has been going since July 2010, with a mix of pieces about music, following a lower-division football team (Mansfield Town), travelling on London Underground, and one (so far) customer service nightmare. A few years ago I moved to Turin and the blog went a bit quiet. I’ve now reactivated it, as I’ve got some new things to write about, including following a Serie A football team (Torino) and travelling on the Turin Underground.

If you’ve been reading, thank you, especially if you’ve commented either on or off the blog. And if you’ve been waiting for some new pieces, sorry about the slight delay.

So that’s the plan, and it will keep going for as long as I’m enjoying it!

Things that never happened in pop music No 2. CBS offices, New York, early 1960s. A senior executive: “We’d very much like to sign you. Just two conditions. One, lose the mouth organ – sorry, the harp. Maybe get a kazoo. Or even better, a harp! Two, get your adenoids fixed. We’ll cover that.” It’s unlikely that this was ever said.

Things that never happened in pop music No 1. It’s the final day of recording for Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. Bryan Adams is doing his vocal for Everything I Do. Someone says: “Bryan, that was absolutely awful. Why don’t you go home and come back when your throat’s better?” No-one said this.

Italians like to be prepared. This is my main observation about their principal behavioural characteristics, based on 12 years living in Turin. In support of my thesis, the standard greeting when answering the phone, the equivalent of ‘Hello?’ in England, is ‘Pronto’ (‘ready’, i.e. I’m not only here and sentient, I’m actually fully geared up to speak to you, whoever you are). Prepared not only for life’s more serious and unpredictable hazards, nor even for more foreseeable events like the weather (umbrellas and thick padded coats are very popular), but also for life’s more mundane activities – getting off an underground train, for example.

Twelve years is a long time, but if I remember correctly, exiting the tube in London was a pretty relaxed affair. You sat in your seat until the train stopped, then stood up, ambled over to the door and, barring any major obstacles, stepped out onto the platform. The trauma quotient was on the low side.

Not here. In Turin the perils of being unable to make good your escape from the train require that you stand up at the stop before the stop you want, or even better before that, move purposefully towards the doors and plant your face right up against the glass. A good deal of jostling occurs as everyone has the same idea. So if I’m waiting to get off at my stop, I’m frequently blocked by clusters of passengers waiting for the next one. The etiquette in this situation is to ask the most irritating question in Italian communal life: ‘Scende?’ (‘Getting off?’).

I’ve timed the period that the doors remain open, and it clocks in at around 20 seconds. Almost long enough to saunter down the entire length of the carriage, have a friendly conversation about the weather and play a quick game of chess.

But the good people of Turin are apparently petrified about being blocked in and stuck on Line 1 of the Metro for the rest of their lives. I used to tell them not to worry. If I’m blocking their exit, I’ll get off the train at next the stop and let them out before getting back on myself. These days my reply to ‘Scende?’ is usually ‘I don’t know’. Just to be annoying, you understand.

Euros cliché (I’m watching on RAI 1 in Italy, but the pictures are probably the same everywhere). Camera zooms in on a group of fat blokes or excitable young women. They suddenly realise that they’re on the big screen and promptly go crazy, because this is an important life event. Camera immediately cuts away. This is the director saying ‘For God’s sake, don’t be so silly’. Every time.

For many musicians, a job pays for our passion and enables us to make the music which people don’t buy in sufficient quantities. If we’re lucky, the job we do fulfils many, maybe most, of our needs – social, intellectual, career, financial.

I was very lucky. I’ve done many jobs over the last 40 years and enjoyed, even loved, most of them. But there was something special about the first one, and my first was the best. At the age of 25, in 1982, after four years studying music and a year just knocking about trying to decide what to do with my life, I got the job of Music Officer at the Dovecot Arts Centre, Stockton-on-Tees. One cold, smoggy February morning I got a train up to Stockton for an interview and came back to London with a job in my pocket and an enormous smile on my face.

For the next eight years that place was my life. I spent my days there, my nights there and my social life there, and never felt for one minute that I’d rather be anywhere else. My friends congregated there for events, my girlfriend was a fixture for music nights, and people I worked with and met during the week are friends to this day.

My brief as Music Officer was simply to get people involved in the Arts Centre – as participants in classes and courses, as attenders of workshops and as audiences of concerts, of jazz, folk and classical music. Back in the early 1980s pop music in arts centres was a no-no. I felt differently. As a musician and music student I could justify the quality of a lot of current pop music against other forms of music, so we went our own way.

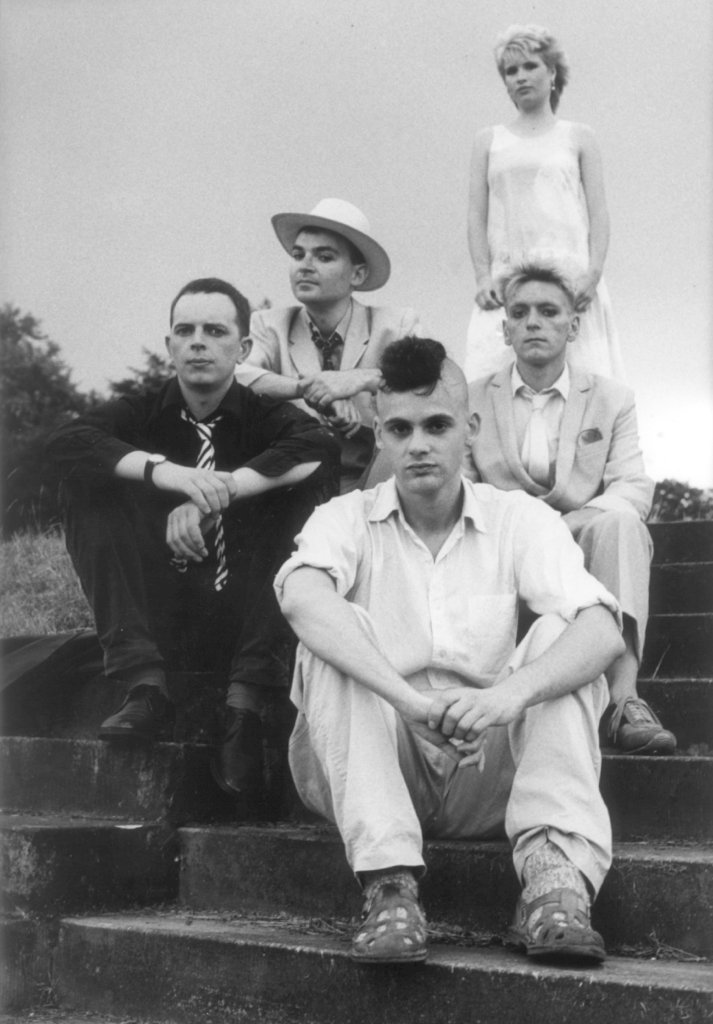

In autumn 1982 I started putting on local bands. This was anathema for an arts centre in those days, but there was a vibrant local music scene and I started branching out to up-and-coming indie bands on the national circuit. After a couple of abortive attempts at finding embryonic indie bands who would draw an audience in Stockton, I hit on Dislocation Dance as the band that would attract a crowd and deliver an evening of quality music. It was the biggest venture (and risk) in my time there until then. I remember we paid £200, which for the Dovecot in those days was a massive fee but totally justified. We got a big audience, considering that the venue’s (official) capacity was around 200.

This is the story of my brief association with Dislocation Dance and my rediscovery of the band many years later. From time to time joyful moments come along, and 15 September 1984 was a day when my destiny and Dislocation Dance’s crossed for very different reasons. That day was not only a delight but has been locked into my memory for all the years since then, and is clearer in my mind than many things that happened last week.

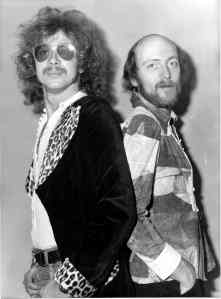

Dislocation Dance and I have some history, and the background to this event is my seeing the band supporting Orange Juice, at that time ‘my’ band, at North London Polytechnic on 26 February 1982. They were interesting and intense, playing songs with a hard jagged edge and lots of energy. Their jazz leanings at the time were not obvious, emerging in full only when they released the album Midnight Shift on Rough Trade Records. It was spiky, angular, classic support band material of the time, real John Peel fodder. I remembered their sound without particularly remembering the songs but made a mental note to look out for them in future.

Fast forward to 1984 and Cleveland, North East England. On the day of a concert I would come down from my office at the Dovecot around 4pm to greet the band, in this case arriving from Manchester, oversee the load-in, which was almost directly into the hall, supervise the souncheck to make sure everything was running on time and there were no problems, and then brief the band about onstage time and practical details. After the soundcheck, I went up to Dislocation Dance’s small dressing room to chat and talk about the running of the evening.

The band’s public face was Ian Runacres, who I got on with instantly. Unlike a lot of visiting musicians, he was co-operation personified, the group’s Paul McCartney figure in terms of charm, diplomacy and good humour. When I admitted that I was a big fan, Ian asked me if there was anything I particularly wanted them to play. I got the impression that they could easily pull out any song from the bag of their enormous repertoire, that it was all rehearsed up to performance standard, so when I said With A Reason, Ian kindly promised to ensure that it was on the set list.

Aside from the local scene, Stockton (and indeed the county of Cleveland) had been starved of good-quality pop/rock music, apart from cover or tribute bands. The great thing about the audience there was that they were so open and honest, no bullshit, and they responded enthusiastically to the events I had started putting on. When Dislocation Dance came, I noticed that as well as appreciating innovation they also responded to good playing and really loved and respected the band’s class.

So, the concert. The opening song, Tenderness, set the tone for the evening, and got an ecstatic reception. One song in, the band had already won over the audience, and continued with a selection of songs from Midnight Shift, earlier unreleased work, and jazzy instrumentals reminiscent of film scores. Many of the Dovecot regulars, music fans, people I knew, realised that they were in the presence of quality songs and musicianship – some even got up and danced, an activity that usually took a lot of warming-up in slightly inhibited Stockton.

The two-singer approach worked perfectly. Ian Runacres was clearly the bandleader. Standing centre-stage, he had a relaxed presence, easy movement, a beautiful voice and an understated charisma about him. His counterpart, Kathryn Way, doubling on alto saxophone, was more demonstrative visually, with an unselfconscious style of dancing, in many ways the antithesis of the classical indie kid who was generally reluctant to move his (usually his) body in any expressive way. Her classic light indie voice had a breathy 60s pop/soul influence and fitted beautifully in unison or harmony with Ian Runacres’. Trumpeter Andy Diagram (later of Pale Fountains and James) provided the jazz and weirdness element as well as filling out the sound on keyboards, and a solid rhythm section of drummer Richard Harrison and bassist Paul Emmerson were the bedrock of the music, contributing to a light funk grooviness.

Some standout moments: the achingly sad Sun Won’t Shine and the blissful It’s No Wonder. The emotional highlight of a very generous set (about an hour and 15 minutes) was when, forty minutes in, they unleashed When, an astonishingly beautiful song of loss and longing. There’s a grainy video of that song on YouTube, taken from an amateur recording of the whole concert, and I always revel in the endlessly repeated choruses at the end. And then finally, as promised, With A Reason, an anthem of glorious optimism which had the audience yelling for more.

In fact, at the end they wouldn’t let the band go, and after an encore, an African-inspired guitar and drums workout followed by the should-have-been-a-hit Show Me, the opener, Tenderness, was reprised. The audience would have been happy if Dislocation Dance had played all night, but the band left them just in time, wanting more.

Other observations. The body language, lots of eye contact, smiles of delight, glances between the musicians showing the sheer pleasure they took in playing together that evening; this was a band at the height of their powers, and they were clearly overwhelmed by the audience’s response.

People were talking about the event for weeks afterwards – people I bumped into in the street, local musicians who had seen something new and different, colleagues who recognised that the arts centre had moved up a gear and was now something more credible in terms of indie pop bands. That night with Dislocation Dance set the Dovecot off in a new direction which included the cream of the indie scene: Black, The Housemartins, Edwyn Collins, The Triffids, Felt, so many more, countless bands, many of whom stayed over at my house in Billingham.

The band came back a year later, with a new singer and a saxophone player. They were as good as before, in a different way. The vocalist Sonia Clegg had a gorgeously rich soul voice, in contrast to Kathyrn Way’s more classic indie phrasing. That concert is a story for a different article, which I probably won’t write.

Many years later, my own band followed Dislocation Dance’s trail to Japan, playing in the same venues for the same promoter. On the back of that tour, Ian Runacres reconstituted Dislocation Dance in partnership with Phil Lukes and released the albums Cromer and The Ruins Of Manchester, which are the equal of the original band’s output.

On a personal level, some time in 2017, now living in Italy, I made contact with Ian after a nostalgic evening watching my video of the concert, drinking red wine (pass me that bottle of…) and listening to their albums, leading to the start of a valued friendship which continues today.

So, loved and lost, and found again. A great, great band, probably too eclectic for fame, and thank God for that!

Molinette Hospital, Turin, February 2022

I’ve noticed that the nurses address the other patients in my room by their first names, but me as Jones (no ‘Mr’). I explain that Jones is a surname. There is a similar first name John (or Jon), but mine is William. William Jones. Sticking with the surname idea, they start calling me John. I should have kept quiet about him (or Jon). Sometimes Italians reverse the order, usually in official situations, but this isn’t very official. So I remind them again that my first name is William. Now they decide that I’m Williams. I explain that Williams is a surname, but it’s not my surname. My surname is Jones. So it’s back to Jones. Then I’m deemed to be ready to be let loose on the outside world with my bewildering variety of names. I just hope they discharged the right person.

I was talking to an Italian student about English humour. As an example I used the Paul McCartney joke. OK, it’s not exactly a joke, it’s a pub quiz question, but it appeals to the English sense of the ridiculous. (What’s Paul McCartney’s middle name? After several wrong answers… Solution: Paul. Uh? Yes, he’s James Paul McCartney.) My student had a bent for lateral thinking, so I thought she would enjoy this. Her first answer was ‘Mac’. Creative enough, but I had to point out that ‘Mac’ was part of his surname and couldn’t count as a middle name. After several wild guesses, the student forced me to reveal the answer. After a moment’s reflection she said: ‘So he doesn’t have a first name.’ Me: ‘What do you mean?’ Student: ‘He doesn’t have a first name, only a middle name and a surname’. And that could be the difference between English and Italian humour.

If you’re of a certain age, you’ll remember that in the old days Frank Lampard was Frank Lampard Junior, and his dad was Frank Lampard. Now it’s all different. Frank Lampard is Frank Lampard, and Frank Lampard is Frank Lampard Senior. As Greavesie used to say: “It’s a funny old game, football, Saint. In fact, football, it’s a funny old game”.

Great, but weird, customer service. In my home village of Llanfairpwll, Anglesey (the self-styled ‘small village with the big name’ – I’ve only given you an excerpt), there is a cafe in a shop called James Pringle Weavers, right outside the station.

Me: A cup of tea, please.

Shop Assistant: Anything else?

Me: No, just the tea.

Shop Assistant: That’ll be £1.50 altogether.

At the end of an audition for a new guitarist for my band in the early 1990s, the candidate (whose name shall remain confidential) turned to me and commented: “You look like him, you do.” In the absence of any prior reference to anyone who might be described as ‘him’ I asked ‘Who?’ The reply nonplussed me. “That Robert Fripp”. This was the first time the ex-King Crimson leader had been mentioned during our meeting, and ‘that’ suggested that not only we, but people in general, had been talking about him, and for quite a long time. The aspiring axe-wielder didn’t get the job. Still, I can see the resemblance.

Do song lyrics matter? In general, for me they do, and most of my favourite songs have great music and words that mean something to me. Having said that, a few songs I love have lyrical content that is arrant nonsense. Exhibit 1 for the prosecution is Reward by The Teardrop Explodes, a magnificent blast of music, if not of literature. OK, it’s an easy defence to refer to Julian Cope’s outlandish medicinal consumption, but that’s no excuse. Let’s look at the evidence:

Bless my cotton socks (no-one says that these days, except possibly your great-grandmother; it’s no way to start a song) I’m in the news (why? for what notable event/activity? – not specified)

The King (who?) sits on his face (impossible) but it’s all assumed (what is?) (Another version of ‘but it’s all assumed’ has ‘buttons all askew’ which makes as little sense)

All wrapped up the same (what is all wrapped up, and the same as what?)

They can’t have it (who, and again, what can’t they have?), you can’t have it (ditto), I can’t have it too (surely ‘either’?)

Until I learn to accept my reward (what reward? for being in the news? and why should I have to learn to accept it? I’d be grateful in any case)

You’ll get as much solid information from the subsequent verses (i.e. zero, unless you’re sharing Mr Cope’s prescription).

The fact that this song reached No 6 in the singles chart shows that few listeners share my rather pedantic interest in the literal, or even metaphorical, meaning of the lyrics. Which disproves my point.

Having lived in Italy for nearly ten years, I must be pretty happy with my lot. I enjoy a good standard of living and a pleasant climate, and I meet a lot of nice and interesting people. The only downside is the question of how a nation with such copious layers of bureaucracy can be so utterly inefficient. But a moment’s thought later, the answer is obvious. Simply reverse those two statements and insert a ‘because’ between them, and there’s your answer. In a country where you need a health card, a tax code, an ID card and proof of residence if you so much as want to fart, Italians are incredulous when I tell them that UK citizens don’t have identity cards. They wouldn’t accept them. But how can you prove that you exist? is the usual response. I generally turn the question round and ask them if they think I exist. The answer is almost always ‘yes’. Having persuaded them that my bizarre claim isn’t some kind of ironic English joke, I then induce a state of total shock by saying that when I lived in England, I usually went out without carrying any form of identification at all (being white anyway, I probably wouldn’t be stopped by the police and asked to show my credentials) – the only exception being if I was going abroad, in which case a passport was always useful.

It’s difficult to hate something in its absence, but my biggest bugbear here is Italian customer service. Good customer service in these parts isn’t about satisfying, or even serving a customer, it’s rated by how successfully the reams of paperwork have been completed. This issue is the direct descendent of the bureaucracy nonsense I’ve just described. This is how it works in practice.

A few weeks ago I received an invitation to apply for a Covid vaccination, being in one of the priority groups. I completed a form on a website and a few weeks later received an appointment for Friday 9 April at Juventus Stadium (as it’s euphemistically called) to receive my dose. (I refuse to use any monosyllabic word beginning with ‘j’.) The time of the injection was to be 12.18pm. I was immediately suspicious. 12.18pm doesn’t exist here. The nearest equivalent on the Italian clockface is ‘When do you fancy?’ or, more precisely, ‘some time next week’. But no, it was true, because the day before the appointment I received a reminder to come at exactly this hour. So, armed with all the proof of my existence I could muster, a printout of the reminder email and my ancient Italian mobile with the same in text message form, I took a very expensive taxi ride to the ‘stadium’, arriving at 11.48am. Of course, things were running late. Apparently there were ‘problems’. But finally I was ushered in through the gate and ticked off the checklist, to be shown to a waiting room, which was some kind of elaborate tent in the Juventus car-park. Waiting room is the right name, as I languished there for nearly two hours, before being summoned, not by name, but by the now long-departed hour of 12.18. Luckily I was the only person called 12.18.

So far, so smooth. But here things started to go wrong. I wasn’t on the list. Digging out of my bag all the documents I had carefully chosen as evidence, and waving my invitation in the form of two different media, I stood my ground. Bad news. According to this (second) list I didn’t exist after all, at least not in terms of getting vaccinated. My usual approach in this kind of situation is to ask a couple of questions very calmly and reasonably. And then get angry. Neither part of this strategy worked. Apology? Are you crazy? Explanation? You’re joking. Just the classic Italian body language of excuses – the shrugged shoulders, the little puffs of air, the rapid hand movements, all of which translate into ‘not my fault, guv. What’s more, no idea whose fault it is’. At these times I wistfully imagine I’m in New York, or even in parts of London, and some concerned individual soothingly saying ‘I’m really sorry, Sir, this is unacceptable. Give me a moment and I’ll make a call and fix a new appointment for you. Please take a seat.’ Not here. Here it’s ‘they sent out a cancellation yesterday, two hours after your confirmation, but they didn’t tell us what to say to people who turned up’. Naturally it’s the poor staff who are the victims here, not the customers. To be fair, there was some guff about me no longer being a priority since some governmental change of mind yesterday, but that’s it. Of course, there was no cancellation on my phone or in my inbox. What do I need to do now? Search me, mate.

So there we are. Some 20 euros taxi fare lighter and half a day’s work lost, I am still unvaccinated and possibly constitute a grave peril to the ageing Italian population. But I’m going to console myself with a posthumous challenge to Rene Descartes about whether, in the absence of an Italian ID card, he truly existed. And whether he ever got vaccinated.

Good question. Long story. Short answer.

Good question. Long story. Short answer.

Having signed up for what I thought would be just a year in the ‘real’ Italian capital, I had a checklist of must-do activities and must-visit places. It turns out that I underestimated my stay sevenfold (so far), and many of these tasks are still staring accusingly at me from the list.

They included taking in an Italian football match, apparently perversely since I’d always found continental football indescribably boring. Can’t see the attraction of Barcelona, to be honest – all that short passing and fussy movement, usually going nowhere. In fact the very term ‘European football’ fills me with a sense of existential weariness, born of dreary UEFA television nights in the 70s and 80s where some Belgian gang takes on a bunch of Austrian no-hopers, invariably in the murky light of a half-empty stadium, backed by an unrelenting accompaniment of claxons and fireworks, and both sides gain a valuable point by virtue of failing to score. The audience is hemmed in by high fencing.

But going to a Serie A (or even Serie B) game would be more a cultural than a sporting experience. I would be an honorary footballing anthropologist, observing some of the different ‘behaviours’ of Italian crowds compared with English.

A bit of background here. Ten years of supporting Mansfield Town home and away before giving up on them had left me with a rather peevish sense that I’d paid my debt to society, and now deserved some solid success. Making the play-offs of League Two (otherwise known as the fourth division) didn’t count as solid or any other type of success. So for English purposes I switched my affections to Manchester United and, while not getting as emotionally involved as with the Stags, generally wanted them to win and was annoyed when they didn’t.

Here in Turin the options are clearer – it’s Juventus or Torino. OK, some people support the odd Milan team or Napoli, but these are eccentrics in a city divided into two. It should have been an obvious choice, but after my decade as a Stagsman I was instinctively inclined to the underdog. There were practical reasons too. Torino’s Stadio Olimpico is just a few minutes from the city centre, it’s easier to get to, no problem buying a ticket, and cheaper too, especially since they were in Serie B when I arrived.

There was a history, too. I hadn’t done any research at the time, but later learned that the ‘Grande Torino’ team of the late 1940s – reputedly the best in the world – won Serie A five times in a row, provided ten elevenths of the Italian national team and was tragically wiped out in an air crash just outside the city, a disaster that still resonates with the population of Turin today.

Getting a ticket was a bit different from turning up at Field Mill on a Saturday afternoon with ten minutes to spare, waving £8 at the turnstile-keeper and taking your pick of seats. Italian bureaucracy (more of this another time) involves providing just about every personal detail you possess, passport, address, the lot. And then displaying it all again on the day if you took the precaution of buying your ticket in advance. As it happened, I needn’t have bothered with the advance purchase bit. When I arrived about half an hour before kick-off, the stadium was more or less attractively empty.

The ground is a step up from Field Mill, definitely, but is blighted by that oval seating arrangement which, like the old Stamford Bridge of the 60s, places the most dedicated fans at opposite ends farthest away from the action, separated from the pitch by a decommissioned race-track. Something to do with the Olympics, I think.

When I made the decision to go to this game, I didn’t even know Torino’s position in the league. I found a Serie A table, but they weren’t there. Must be some mistake. But no, a visit to the club’s website clearly showed them sitting comfortably at the top of Serie B. In a way, this was a relief, as I was more likely to see a victory and, this being April, something was probably at stake.

I knew none of the players but enjoyed the announcement of the squad at ten to three. The away team (on this occasion the not-very-mighty Gubbio) are given a surly, rapid, surname-only introduction. By contrast, when it’s time to announce Il Toro, the announcer suddenly brightens up (actually, make that ‘goes crazy’) announcing players’ first names only for the crowd to yell the rest. The biggest cheers came for our number six Angelo Ogbonna (a rare Serie B Italian international) and local hero, number nine Rolando Bianchi. The accompanying pictures were helpful, with ancient coach Giampiero Ventura looking like a cross between my old Mansfield gaffer Andy King and a bloodhound. (Try to ignore the genealogical implications of that union.) I was intrigued to see what Juan Ignacio Surraco and Cristian Pasquato could do, and felt that the name Francesco Benussi carried a bit more of a ring to it than his erstwhile Mansfield counterpart between the posts Kevin Pilkington. Anyway, let the action begin.

Ogbonna was immediately impressive as centre-back, reminding me, with his effortless style, poise on the ball and plentiful time, of Bobby Moore – the way he always looked up and around, instead of down, and the stylish ease with which he dispatched the ball. Bianchi had been short of goals recently and missed a sitter right in front of me but, willed on by the crowd, bagged a brace (football cliché alert – that’s two goals). Surraco and Pasquato answered my question by both scoring, the remaining two goals in a 6-0 drubbing (clicheville again) coming from Mirko Antenucci.

I congratulated myself on my wise investment of 15 euros, and decided to go again. Slight problem. Without yet realising it, I was hooked. ‘Again’ was Reggina. 1-0 to us. You see, now it’s ‘us’. And again. 2-1 against Crotone. And again. 3-1 versus Padova. Yet again. We trounced (ouch!) Sassuolo 3-0. Which brings us to the final game of the season. And for the first time I couldn’t buy that easy-to-get, dead-cheap, oh-so-convenient ticket. The game was sold out, and I had to watch in a pub. 2-0 against Modena and we’re up. I didn’t even know about the parade through the city so didn’t turn up. Determined never to miss out again I decided to invest in a season ticket for our return to Serie A. Should be simple. In Italy? Well, that’s another story.

So that’s why. Actually it was quite a long answer, wasn’t it?

Sometimes I try to recapture a feeling I had years ago. My mood, my attitude, my outlook – what it was like to be me back then. It’s difficult to do, and impossible to describe in words. But often, if I can reconnect to a song or piece of music I associate with that time, then the music acts as a bridge and takes me back to a particular place or situation, and I get a glimpse, for a fleeting moment, of that feeling. In the absence of my own tardis, music is the best form of time travel I know.

In 1980 I was a postgraduate music student at SOAS, London University. In order to pay the course fees, without the luxury of a grant, I was working as a kitchen porter in my college for four hours a day and as a barman at the University Of London Union most evenings. In theory this was fine, but it left me very little time to be a postgraduate music student at SOAS, which was, after all, the object of the exercise.

By spring 1981 I had risen to the dizzy heights of Senior Evening Barman, largely by virtue of being able to serve five people at once, form a notional queue from the heaving mass of bodies in front of me (“It’s you, then you, then you, then you, then you.”) and sprint down to the cellar and change a barrel only fractionally more slowly than the speed of light. I could also deflect some of the aggro of disaffected drinkers away from my colleagues, in part because, as a skinhead, I looked like a thug. I still treasure this frankly negative appraisal of my character from a frustrated customer: “I think you are a very rude man”. Spot on.

ULU back then was host to an amazing programme of top indie rock and pop groups. On Friday and Saturday nights the bar would be crammed wall to wall from early evening until late closing, and you’d finish the evening soaking wet, exhausted but still feeling hyperactive, then get home around 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning. For all-nighters, double the wet, exhaustion and hyperactivity, and change the hour to breakfast time.

The prized shift was Sunday afternoons, when trade would be quiet, the atmosphere relaxed, and you’d have a chance to wind down and chat to colleagues, many of whom were also friends, without a mass of punters hurling insults at you.

On one such Sunday in early spring 1981 the warm afternoon sun was streaming through the windows of the bar and I happened to catch the strains of Gilbert O’Sullivan’s What’s In A Kiss? ringing out of the PA from the jukebox in the next room. And now I can remember the exquisite feeling of that day, and of those days. One of endless possibility, curiosity about where life would take me, a hint of insecurity about soon having to get a real job and stop pretending to be a postgraduate student, and a sense that almost everything was ahead, and very little behind. The sound of that song stood out from everything I was hearing, out of time and place for 1981 – not funky, not post-punky, not jazzy, it was clear, bright, almost translucent, a delicious mix of melancholy and optimism. It matched both my own mood and the light flooding into the room, and I went straight over to the jukebox to play it again. And again.

By 1981 Gilbert O’Sullivan had been out of the picture for a few years, embroiled in the inevitable legal wrangles that followed musical success back in those days. So my first reaction was: “I know that voice. Ah yes, him. Whatever happened to him?” At that time, everyone seemed to be coming back. As well as O’Sullivan, John Lennon’s glorious song Woman had recently been in the charts and was still on that same jukebox, and my favourite band Strawbs were touring again after a long break.

Factcheck for any popkids who were born too late: Gilbert O’Sullivan back in the early 1970s was massive in the UK, in America and in many other places around the world – a pop superstar. A string of number one and Top Ten hits had made him the biggest solo artist of his day.

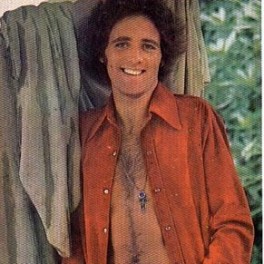

Like Elton John he had started the decade as a serious, ‘alternative’, credible singer-songwriter, in the same niche as, say, John Sebastian, James Taylor, Nick Drake and Jonathan Kelly – this was the indie scene of those days. In an era when the regulation clobber of rock musicians was a woolly sweater, an Afghan coat, shaggy hair and a beard, O’Sullivan had adopted a unique and striking look – that of a 19th century street urchin, with pudding-bowl haircut, cap, baggy trousers, braces and hobnail boots, a rascal straight out of Oliver. Some have described that image as limiting his appeal and distracting attention from the music, but for me it’s a brilliant creation, anticipating the individuality of punk: be different, be yourself, use whatever comes to hand – rags, pins, second-hand clothes, anything. It’s the classic attitude of an ex-art student – you yourself are the work of art as much as your music.

Chart hits and a change of image soon altered my perception, and I remember being mildly irritated by O’Sullivan for having kept my own favourite ‘serious’ bands off the top chart positions for weeks on end. Top Of The Pops back then was like Division 1 in football, and we all passionately followed bands and supported football teams – in my case, sadly, my home town team Chester (Division 4). My friends and I had now rather snobbishly decided that Gilbert O’Sullivan had become a middle-of-the-road balladeer, making songs for teeny-boppers and their mums and dads. (My own father suffered a similar fate. A lover of Abba’s music, he was affectionately ridiculed by at least one of his children for his bland taste, only proving himself posthumously to be an arbiter of the cool and classic when the Swedish popsters came back into fashion in the late 1990s.)

To quote What’s In A Kiss?, it was ‘really rather stupid of me’ to deny how much I actually loved and admired Gilbert O’Sullivan’s songs, since I could still sing along with them nearly forty years later. Alone Again (Naturally), Nothing Rhymed, Clair and Get Down were locked into my memory as all-time pop classics, and I could predict every twist and turn of the lyrics and music.

So thirty-seven years later, just a few weeks ago, I decided to revisit What’s In A Kiss? – go back to that Sunday afternoon in the ULU bar and try to work out why this song had remained lodged in my brain and in my heart, off and on, for so long. At the start O’Sullivan sets up a basic three-chord sequence that runs through most of the song. It’s a simple and beautiful concept clothed in the most gorgeous of melodies. Three verses, a couple of middle eights and an instrumental, and you’re out in less than three minutes.

His voice is unmistakeable. It has the purity of a choirboy, but with a slightly hard and plaintive edge. There are echoes of both Lennon and McCartney, of Morrissey (years in advance), and a nasal quality reminiscent of Bob Dylan. He’s always totally in tune, thankfully almost completely vibrato-less, and has a way of phrasing that pulls the words this way and that across the beat, so that you feel he’s talking as much as singing.

Intrigued by what I’ve missed since 1981, and further back to those prehistoric early 70s, I’ve watched numerous documentaries, interviews and concerts. What have I learned? First, what an astonishing performer. Seeing him bound on to the stage at the Royal Albert Hall and burst into the upbeat, latinesque Matrimony, jumping on top of the piano and witnessing the joy and love of the audience, you just wish you were there, every time.

Watching him play live, as I happily had the chance to do recently, he’s always completely ‘in’ the song – never going through the motions or putting on a show. What you get is the complete sincerity of the person who wrote it and still believes in it. And this goes back a long, long way. On the 1978 BBC2 programme Sight And Sound you’ll find O’Sullivan delivering a blistering set which mixes the big hits with some less commercial offerings from his new album Southpaw, backed by a ready-made, fully-functioning working band called Wilder which he’d chosen in place of the standard session-men support fodder.

He writes and sings in an unusually conversational, colloquial way. In a song like We Will, he’ll stretch the lyrics across the beat, cram in crowds of words between the beats, pause and then catch up as the words cascade down – it’s not so very different from rapping, albeit from a very different musical perspective.

Then there are those enormously long verses. In Alone Again (Naturally) they seem endless, allowing the writer to construct a narrative and pack in a whole stack of information. Many of his best songs don’t have conventional, blockbuster choruses either, but just use a short and simple phrase as the recurring hook, often the title of the song itself, like Alone Again. It’s always enough.

The voice, incredibly, is unchanged after all these years. O’Sullivan is modest about his vocal ability, but he’s fully able to turn on the rock in a song like Stick In The Mud, or croon a beautiful ballad, while in the outro to The Niceness Of It All and in Bear With Me he’s a wonderfully authentic soul singer. George Benson wanted to cover the latter song, and you can’t imagine George doing it any better. The RTE programme Out On His Own shows O’Sullivan wowing audiences in Tel Aviv and London, talking about the headstart his mother’s sacrifices gave him in his musical career, and in particular about his focus on the present and the future rather than the past. Many people don’t realise that he’s continued writing for the last forty years, working eight hours a day to craft an incredible repertoire of work, including songs which easily match those 70s classics – songs like Miss My Love Today, For What It’s Worth, Where Peaceful Waters Flow, At The Very Mention Of Your Name, All They Wanted To Say, No Way, The Whole World Over and many, many more.

Viewing this wealth of material I’ve found him a thoroughly likeable character; bitter and cynical, yes, about his level of recognition today, justifiably arrogant about his work and his worth, but decent, honest, articulate and humorous in a quirky way. Someone you’d rather have on your side than against you.

I bought my first record in 1962. This means that I’ve been a music fan for over 55 years, and I would unhesitatingly describe Gilbert O’Sullivan as the greatest singer-songwriter in English popular music. If that sounds like an extravagant claim, let’s examine Exhibit A in the evidence for the defence – the song We Will. Paul Gambaccini has described Nothing Rhymed as one of the greatest songs of all time. I would put We Will up there in the same bracket. It’s an astonishing piece of work, all the more so for a writer in his early 20s – the bitterest-sweetest tale of achieving consolation through the mundanity of family life and old friendships. Referencing bedtime rituals, cereal for breakfast, visits to grateful aunts and uncles and playing football with old mates, I read the song as a kaleidoscopic journey from childhood to old age, three crystal-clear snapshots in just three verses. It features those sinuous, long and endlessly weaving lines which enable the singer to build an argument, add little interpolations and hesitations and throw in casual asides, the “then again”s and “on the other hand”s of everyday conversation, as they climb and climb to a climax and then fall away in quiet resignation. The two-word chorus, the song’s title, is delivered by a children’s choir and quietly echoed by the singer. It’s sublime.

The journalist and musician Bob Stanley, writing in The Guardian, describes finding the song by chance and being ‘knocked sideways’ by it, listening to it every night before bed to survive a bad time – which is easy to imagine, as it’s simply a song about being human and trying to get through life intact. There couldn’t be any greater compliment.

Exhibits B to Z are on YouTube, Facebook, and all those other places ‘out there’. It’s admittedly not the most scientific research base, but in the hundreds, thousands of comments about Gilbert O’Sullivan’s videos and concerts the most frequently recurring word is ‘genius’. You’ll find countless heartfelt testaments to how much his music means to people, and I hope Ed Heider won’t mind me lifting his post from YouTube: “Gilbert, you changed my life to a better feeling about all of its aspects, your songs, sound and music made me start every morning as a new person born again”. If, as a songwriter, you can look back at your career and tell your grandchildren that you changed people’s lives, that’s pretty much ‘job done’, I think. Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, I rest my case.

When my band’s profile was higher, I often used to be interviewed by fanzines, bloggers, indie magazines and even, once, by one of the ‘real’ music papers. A frequent question was whether there was any song I wish I’d written. I always replied that I was very happy with most of the songs I’d created myself, and refused to be drawn into this strange form of compositional envy, harmless though the question was. It didn’t matter to me whether I’d written a great song or if any other person had done the job – only that someone had written it. So no. With What’s In A Kiss?, We Will and so many others, anyone would be proud to have their name on those timeless, universal songs. They’re not mine, and I don’t care. I’m just happy and grateful that they exist, and that the writer was Raymond O’Sullivan.

I’ve often wondered what it means to follow a football club. Of course, I know what it means to me – a bit more of a commitment than some frippery like a career, or marriage, say. No, it’s the actual qualification as a fan that puzzles me – are you one because you say you’re one, or is there some litmus-like test which identifies you as such: dip me in the solution, I turn yellow so I’m a Stag.

I’ve often wondered what it means to follow a football club. Of course, I know what it means to me – a bit more of a commitment than some frippery like a career, or marriage, say. No, it’s the actual qualification as a fan that puzzles me – are you one because you say you’re one, or is there some litmus-like test which identifies you as such: dip me in the solution, I turn yellow so I’m a Stag.

I once worked with someone who everyone knew was a lifelong Sheffield Wednesday supporter (his life at that point amounting to slightly short of forty years). We were aware of this because he’d discuss the game on a Monday morning, talk knowledgeably about the players, say things like “What we really need right now is a right-sided midfielder”…but not actually go to any matches. Pressure of work, often at weekends, other priorities. I, however, who’d started supporting Mansfield Town on moving to Nottinghamshire, and was an ever-present, home and away, for several seasons, was somehow not quite the real thing, but a Johnny-come-lately fairweather friend. He was a true supporter, blue and white through and through, whereas I was some kind of mercenary rent-a-fan who at any moment might transfer his affections to Barnet, or Manchester United.

Then there were all those Labour men who wore their adherence to their team like some kind of badge of ordinary blokedom. Everyone had to support someone as proof of normality. Thus we needed to know that Alistair Campbell was a passionate Burnley fan, as if it somehow made him any less of a bastard. Gordon Brown was big on Raith Rovers, scoring points on local allegiance whilst marginally addressing the utter weirdness factor. I’d really rather they’d all hated the game than each having some adoptive football club grafted onto their dysfunctional personalities.

Andy King once said a wise thing at a meet-the-manager-and-ask-him-awkward-questions evening at Mansfield. Addressing some prickly poser about the long-term direction of the club he said: “You lot, you’re the club. Me, the chairman, the players, we’re just passing through.” It’s true, but even players build up an affinity for a club if they’re there for more than a couple of seasons. And when they finally move on they “always look for x’s result first” where x is the club they’ve recently quit for a better deal. It’s a cliché that fickle fans have adopted too.

In a way I envied my friend with his no-commitment, free-as-the-wind approach. He never had to worry about everything going sour. His supporterdom was all in his head (he would say genes), a virtual equivalent of his birth certificate, rather than being measured in hours, (hundreds of) pounds, freezing temperatures and (thousand of) miles.

The last time I saw Mansfield Town play was at Brentford in August 2008, our final season in the Football League. On relegation to the Conference, the better players were sold off, and by the end of our first non-league season I only recognised the name of one player, Nathan Arnold (‘Nay-Nay’ as I’d learned his nickname was). I’d read about some of the others – players who’d dropped down from the ‘real’ league to play for a club who tried to match their lack of ambition, old hands desperately reviving their careers and giving it one last shot, and promising youngsters on their way up. By the time Dave Holdsworth departed as manager, he had seen some 60 new players into and out of the club, like the keeper of some wildly-spinning revolving door of transfers and loan deals. I’d look at the team list in the Sunday papers and think “And who the hell are you?”

Like the sentimental (or dishonest) ex-player, I still look for their result first – well, after looking at the Premiership scores which I already know from the previous night’s Match Of The Day. But when someone asks me who we’re playing on Saturday, I usually couldn’t say. Some Cambridgeshire village in the Blue Square something-or-other league. Hufton? Hickston? Never been there, anyway.

Am I still a fan? I don’t really know. I don’t think I support anyone else, anyway. And if anyone asked who my team was I’d still say proudly ‘Mansfield Town’. But does that make me any better than Alistair bloody Campbell? Probably not.

One of the things about supporting a small club in a lower division (OK, the bottom division) is that you spend a lot of time standing on terraces in small grounds. And one of the advantages of this is that you can actually hear a lot of the specialised language spoken by the practitioners of the beautiful game. Or, at this level, the OK-looking in a good light and after a few drinks game.

One of the things about supporting a small club in a lower division (OK, the bottom division) is that you spend a lot of time standing on terraces in small grounds. And one of the advantages of this is that you can actually hear a lot of the specialised language spoken by the practitioners of the beautiful game. Or, at this level, the OK-looking in a good light and after a few drinks game.

Before the new ground was (nearly) built at Field Mill I’d perch against a barrier near the halfway line for maximum exposure to the advice, instructions and expletives of manager Andy King. This was always entertaining as King enjoyed good rapport and plenty of banter with the home fans, and not only concerning his rapidly disappearing thatch.

Old Trafford may be awesome, but with Alex Ferguson about five miles away from most seats you can barely see his back, let alone hear what he is grunting through his chewing gun. 2,500 people, on the other hand, can’t make a lot of noise, and often, especially during moments of the greatest ennui, they can actually go very quiet.

So when Cardiff were trying to find a way past slow-moving, granite-hewn, one-man wall of defence Brian Kilcline, you’d expect them to vent their frustration in verbal form. You might hope for something as cultured as a piece of Match Of The Day-style analysis from someone called Alan – maybe ‘right, lads, pull him out of position and we’ll exploit the space between Kilcline and the other centre back, and flood forward into the yawning gap that opens up’. (Cue on-screen graphic of a shaded square shape.) Instead, at one of those moments when the whole ground simultaneously decided to go silent, we heard the echoing yell ring out “Get fucking Kilcline”. A much simpler methodology, drawing an ironic cheer from the crowd, who knew that Cardiff had got the wind up. I don’t think they ever did manage to ‘get’ the aptly nicknamed Killer.

Adrian (‘Ady’) Boothroyd was an intelligent right back and a soon-to-be bright, embryonic manager, and it was fascinating back in those mid-90s days to see him still trying to perfect his craft. One Saturday afternoon warm-up before a meaningless end-of-season game I saw Kingy out on the pitch in his tracksuit drilling Boothroyd in a new way of imparting spin to the ball, kicking over it to increase the pace but reduce the flight. Boothroyd practised it over and over again, and I was amazed not only at King’s skill (and coaching ability) but also at the player’s willingness to learn something from the older man. King’s regular instruction to Ady during matches as he fired in crosses on his characteristic overlaps was “whip it”. So regular, in fact, that the crowd often told him before King got a chance. So here was Boothroyd, in his late twenties, learning another way to whip it.

I’ve always wished that TV football programmes would supply a lip-reader to let us viewers know what the players are saying to each other and to the referee. I know there’s a lot of ‘get tight’ and ‘second ball’, and I’m sure this means something important. Sometimes it’s easy to guess the words, but for those that don’t begin with ‘f’, it usually isn’t. At Field Mill, however, you got the full aural effect – no audio-description needed. I know that conversation with the referee often centres on his eyesight, ancestry, body mass index, hair coverage, moral standing or colour. But amazingly, I discovered at Field Mill that players don’t always curse the official. I once heard the erudite Boothroyd deliver the most considered, polite and quasi-legal challenge to a referee’s decision: “Surely not!”

Boothroyd, as a right back, would spend half the match as the closest recipient of his manager’s usually unintelligible instructions. I know that players often pretend not to hear what’s being screamed (or see what’s being mimed) by ex-playing managers frustrated by their latter-day impotence on the touchline. Often these are third-party directives to give team-mates some vital piece of news or information. Boothroyd’s default response was “I’ve told him” before running off. There’s no answer to that, as Kingy discovered.

Whilst verbal communication between team-mates is to be encouraged, it has the disadvantage that its audience includes the opposition. The number of substitutes a team can name has risen in line with inflation from one to two, to three including a goalkeeper, to any old three, to three out of five, and now three out of pretty much anyone who lives in the EU. In the days of ‘any old three’, you’d think most teams would either include a substitute goalie, or at least have in mind someone who would go between the sticks (or what Alan Hansen calls ‘the goals’) in an emergency. Not Mansfield Town, not Kingy. When Stags’ keeper was carried off in some no-hope Auto Windscreeen Shield tie, we expected a fairly swift donning of the green jersey by one of the subs or even onfield players. But no. Cue lengthy debate about who it should be, and careful appraisal of the merits of several candidates for the position before they were for various reasons discarded from the selection process.

By some mystical rite akin to puffs of smoke rising from the Vatican, the gloves were destined for the frozen hands of midfield linchpin John Doolan, the one player you wouldn’t have wanted stuck in the wrong 18 yard box. But Scouser Doolan had already blown any suitability for the task facing him by loudly broadcasting, in tones of rising panic: “But I’ve never been in goal in me life”. Oh. A bit like the “I can’t swim” confession in Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid. The West Terrace was instantly filled with dread, and the opposition bench, sited just in front of them, with a fresh sense of endless possibilities and a hatful of goals.

Tactical instructions, like words of encouragement or abuse, can often be overheard and thus, as David Coleman used to say, ‘telegraphed’ to the opposition. Phil Stant had been a cult hero at Mansfield, largely for his 26 goals in the 1991/1992 promotion season, but also for giving every semblance of madness, and not just through his various entertaining hairstyles. His exploits and personality had earned him the nickname, probably unwelcome to most people, of Psycho. Returning to Field Mill as a Bury player, he inevitably destroyed his former club in a 5-1 win and annoyingly received a standing ovation from the home crowd as he left the pitch early. (I don’t mind sportsmanship, but that’s taking it too far.)

But at the pause for a throw-in, while an injured player was being attended to, you could hear him plot the next goal from a position near the halfway line. Then, as if watching an educational video, you could follow him and his team-mates execute those precise instructions and admire one of Stant’s four goals that afternoon. “Give it Jonno”, Stant enjoined several times (believed to be a reference to Bury player Lenny Johnrose), before outlining what Jonno should do with the ball when it had been thrown to him. (This mainly involved passing it to Stant himself and being on hand if he needed to dispose of it). Whatever the details, it worked a treat, and Psycho, displaying latent coaching potential here, himself went on to manage, albeit at Lincoln.

But my favourite piece of Stags verbiage occurred not on the pitch, but in the dressing room. No, I never got in there. Never really fancied a communal bath in muddy water myself. Characters would arrive at Field Mill and, like O’Neill Donaldson, stay briefly but remain in the memory for much longer. Cyrille L’Helgoualch was a Frenchman, and God knows how he landed at Mansfield Town. But he briefly illuminated the club with some stunning performances and one great long-distance goal against Rochdale. Before the ground was rebuilt, you’d pass the frosted windows of the home dressing room in the West Stand on your way out of the ground, and even see players’ suits hung up on pegs through the glass. Cyrille’s English wasn’t great, and probably neither was his knowledge of dodgy early 70s novelty singles. So one spring afternoon it was somehow touching, and perhaps a little bemusing to him, to hear the strains of Nice One Cyril coming loud and clear through the open dressing room windows. Yes, it had been a nice one. Just one request, if it’s not too late: let’s have another one.

OK, I feel bad about this. There’s a woman travels on the Victoria Line, probably other lines too. The evidence of my eyes and nose is that she has ‘accommodation issues’ and ‘personal hygiene issues’, probably related. She spends time sleeping on the tube. Today there are severe delays, and the platform is heaving. I get down to the end where the front of the train will stop and hope for the best. I’ll be lucky to get a standing space, let alone a seat. The train arrives. God be praised! The carriage that lines up in front of me is virtually empty. I get on and sit down, spread out my paper and relax. Not for long. The stench is overpowering, and it’s clear why this carriage has been virtually evacuated. Oblivious, and draped across two seats, the lady sleeps on, occupying far more space than she strictly needs. Next stop I get out and squeeze into the next carriage, pressed up against the aftershave and rancorous perfume of the working population of Finsbury Park. The artificial smell is foul, but at least purchased.

OK, I feel bad about this. There’s a woman travels on the Victoria Line, probably other lines too. The evidence of my eyes and nose is that she has ‘accommodation issues’ and ‘personal hygiene issues’, probably related. She spends time sleeping on the tube. Today there are severe delays, and the platform is heaving. I get down to the end where the front of the train will stop and hope for the best. I’ll be lucky to get a standing space, let alone a seat. The train arrives. God be praised! The carriage that lines up in front of me is virtually empty. I get on and sit down, spread out my paper and relax. Not for long. The stench is overpowering, and it’s clear why this carriage has been virtually evacuated. Oblivious, and draped across two seats, the lady sleeps on, occupying far more space than she strictly needs. Next stop I get out and squeeze into the next carriage, pressed up against the aftershave and rancorous perfume of the working population of Finsbury Park. The artificial smell is foul, but at least purchased.

I became aware of Jonathan Kelly’s latter pair of albums relatively late. Waiting On you, made with his band Jonathan Kelly’s Outside, and the valedictory Two Days In Winter, came out in 1974 and 1975 respectively, when Kelly’s career in the music business was on the slide. The main factors in his decline seem to have been a lethal mix of drugs, disillusionment, bad management, diminishing commercial success and, ultimately, the lack of a record company that would release any more of his music.

I became aware of Jonathan Kelly’s latter pair of albums relatively late. Waiting On you, made with his band Jonathan Kelly’s Outside, and the valedictory Two Days In Winter, came out in 1974 and 1975 respectively, when Kelly’s career in the music business was on the slide. The main factors in his decline seem to have been a lethal mix of drugs, disillusionment, bad management, diminishing commercial success and, ultimately, the lack of a record company that would release any more of his music.

A friend who, like me, appreciates Jonathan Kelly’s music, knew the two records and told me cheerfully that they “weren’t very good”. Intrigued, I bought them in their new format as a double-pack of CDs, played them and disagreed. I’ve listened many times since and now love them as much as the two ‘solo’ Kelly albums ‘Twice Around The Houses’ and ‘Wait Till They Change The Backdrop’. Waiting On You, in particular, with its light funk and beautiful, soulful singing is, despite its imperfections, a great record, with memorable, heartfelt songs I’ve grown to know very well.

One of the delights of a Jonathan Kelly record comes even before you hear a sound. Scanning the track listing you see some great, tantalising titles. Who is Rabbit Face? What were Yesterday’s Promises? Where, if anywhere, is Sensation Street? And how does one make it lonely?

After Waiting On You’s undistinguished opening track, Making It Lonely emerges quietly from Kelly’s plain voice/piano introduction. It’s a stunning first verse, with a gorgeous, unpredictable, descending chain of chords and a bold, arresting opening line: “I’ve grown so dependent on you”. You’re hooked in immediately by this naked expression of the insecurity of being in love, and by Kelly’s warm, vulnerable voice – that gentle vibrato on “I spend all day waiting at the window” is pure McCartney.

The chorus explains the title, as the singer accepts, even revels in, the loneliness his love has caused – “Making it lonely for myself, no I don’t need nobody else”. The song’s finest moment, though, is wordless. It’s the chilling middle eight, where a glorious key change is accompanied by a truly sublime, simple guitar solo.

Lyrically very evocative of its time (1974, when women in pop were ‘baby’ or ‘girl’), the whole song brings to mind Carole King’s Tapestry, in its predominance of the piano, the subject matter, and the sheer quality of songwriting. Yes, that good. There might be a few bits of performance that wouldn’t have got past the quality control department of, say, Steely Dan (Messrs Fagen and Becker wouldn’t have accepted the bass guitar and piano left hand being so far out of synch, for instance), but even these faults have a certain period charm.

The first time I heard Making It Lonely I played it continuously for several hours, and only moved on because I couldn’t wait to hear the rest of the album. Its wonderful Sunday afternoon melancholy was addictive, and now I often play it late at night, either on the CD player or on my guitar. But singing along I can never match Kelly’s individual phrasing, however well I think I know the song.

The mystery of Jonathan Kelly’s Outside is how he could attract musicians of such quality (Chaz Jankel, a future Blockhead and Snowy White, later of Thin Lizzy, were in his band) and fail to achieve commercial success. Maybe, knowing the strange practices of the music business and fickleness of the record-buying public, not such a mystery after all. And in many ways Jonathan Kelly didn’t give himself the best chance. You can absolutely sympathise with his career choice, though. Longing to play in a band, and deliver the kind of dancy, jazzy-funky soul music of his musical heroes, people like Marvin Gaye, James Brown and Herbie Hancock, the more he strove to achieve his artistic aims the further he left behind the folk audience who wanted to hear the old songs, acoustically delivered.

I’m left wondering how Warner Brothers, according to an interview on Jonathan Kelly’s website, reckoned his voice wasn’t up to it when they were considering him for their label. If he ever gives lessons in not singing very well, I’ll be first in the queue.

Waking up in some outpost of north London with the sun streaming through your window on a burning July day, getting up quickly, radio on, out of the house, the short walk to the station, rippling trees, warm air, people smiling, the feeling that today something’s really going to happen. Down the stairs into the cool basement of the earth, and onto a train that’s not yet sweating with the crowd. Fifteen minutes later, I’m being carried back up to the ground, blinking into the sunlight as part of the mass, looking around at the vivid summer wonder of the streets and parks of central London with the privileged eyes of a tourist. It’s going to be a beautiful day.

Waking up in some outpost of north London with the sun streaming through your window on a burning July day, getting up quickly, radio on, out of the house, the short walk to the station, rippling trees, warm air, people smiling, the feeling that today something’s really going to happen. Down the stairs into the cool basement of the earth, and onto a train that’s not yet sweating with the crowd. Fifteen minutes later, I’m being carried back up to the ground, blinking into the sunlight as part of the mass, looking around at the vivid summer wonder of the streets and parks of central London with the privileged eyes of a tourist. It’s going to be a beautiful day.

It should be that you see lots of famous people on the tube. There are plenty of people who travel by tube, and surely enough of them are famous. But you don’t. Because famous people can afford to travel more slowly. I’ve seen Jeremy Bowen, Evan Davies (on an escalator, holding court to some bored acolyte), and best of all, John Cole. John Cole was my hero, and used to be Political Editor for the BBC. You’d see him standing outside the Houses of Parliament in his special herringbone overcoat, holding forth in his Ulsterman brogue about the issues of the day. And now he’s sitting opposite me, in a sparsely populated carriage, reading a book about politics. How appropriate. Do I talk to him or respect his privacy? Would he like to know about my admiration for his work? Would he appreciate my impression of him? “This is Jaaan Coooole, reporrrting from Westminstorrr. Now baaack to you in the studio Petorrrr.” Before I can decide he gets off.

It should be that you see lots of famous people on the tube. There are plenty of people who travel by tube, and surely enough of them are famous. But you don’t. Because famous people can afford to travel more slowly. I’ve seen Jeremy Bowen, Evan Davies (on an escalator, holding court to some bored acolyte), and best of all, John Cole. John Cole was my hero, and used to be Political Editor for the BBC. You’d see him standing outside the Houses of Parliament in his special herringbone overcoat, holding forth in his Ulsterman brogue about the issues of the day. And now he’s sitting opposite me, in a sparsely populated carriage, reading a book about politics. How appropriate. Do I talk to him or respect his privacy? Would he like to know about my admiration for his work? Would he appreciate my impression of him? “This is Jaaan Coooole, reporrrting from Westminstorrr. Now baaack to you in the studio Petorrrr.” Before I can decide he gets off.

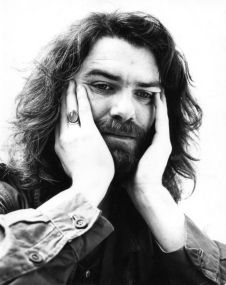

Like many others I fell for The Chameleons in the early 1980s – quite by chance, but that’s the subject of another story. Along with those many I followed them with a passion, even sleeping outside one cold spring night in Leeds when there was no late bus back to Teesside after their show.

Like many others I fell for The Chameleons in the early 1980s – quite by chance, but that’s the subject of another story. Along with those many I followed them with a passion, even sleeping outside one cold spring night in Leeds when there was no late bus back to Teesside after their show.

By the time their third album, Strange Times, came out The Chameleons had built up a huge, devoted live following, had signed to Geffen and looked set for world domination on the scale of U2 or Echo And The Bunnymen. It never happened, and they probably never wanted it to happen. Like many bands on the verge, they were actually on the brink, and personality conflicts, the death of someone very close to them, and possibly a general feeling that they’d run their course led to their split a year later.

The rough-hewn emotion, even desperation, that runs through The Chameleons’ music and knowledge of the time that it was made (the early 1980s) gives their music a darkness and an intensity no-one has matched before or since. It felt, and was, real, different from the fabricated gloom which served as the currency of many bands of that era.

The characteristics of their sound are easy to pin down: two inventive guitarists whose complementary lines weave in and out of each other, giving the music a suppleness and fluidity to match its rhythmic power; the monumental, muscular drumming of John Lever; the bounce of the bass guitar, and the gruff, passionate voice of its player, singer Mark Burgess. How four apparently ordinary blokes from Middleton, Manchester, conjured up such a sound, such beauty and majesty from their hands and voices, is a happy musical mystery.

I don’t hear a weak song in the three albums from The Chameleons’ original, pre-split, incarnation. I love them all, and the one that means most to me is Childhood, from Strange Times. It’s a song I can never listen to in isolation – I have to hear the whole album, and Childhood comes near the end. Of all The Chameleons’ albums Strange Times is the bleakest – the sound of a man, or maybe a band, on the edge of collapse, its monochrome grimness almost oppressive. There are moments of light and love along the way, but the album’s magnificence is in its sense of doom and struggle. And then Childhood comes, its joyous sound like a shaft of sun streaming through a stained glass window. By the time it arrives I’m emotionally exhausted, which is why investing the best part of an hour in waiting for a single song always feels like a very reasonable deal.

The hazy, shimmering opening, with its swirl of characteristically Chameleon guitar, and Burgess’ yelps and wordless singing usher in the band, with that wonderful sprung rhythm they had patented. Lyrically Childhood is unusual for The Chameleons. Their normal subject matter was a kind of generalised, human-condition-related angst, but Childhood deals with the everyday, citing local places (“My life is a Milbury’s home on Hereford Way”), mortgages, weekend routines like cleaning the car, and the importance of keeping that connection with your past (even in the bleakest, strangest of strange times “you have to hang on to your childhood”) – whilst still moving on (“open your eyes or stay as you are”).

Two great verses and a middle eight, and then a glorious epiphany of an ending, this huge belt of chorus after chorus after chorus taking the song to its finish.

It’s a wholly unsentimental song about the past – reflection, affection, but no nostalgia. And then, balance restored after the album’s long emotional journey, one more track – the heartbreaking, valedictory instrumental I’ll Remember. And you do.

Some time in late summer 1988 I received a sales statement from our record distributors. My band’s first album, Let’s Get Away From It All, had come out a few weeks earlier, and I was dreading a similar fate to the debut single which had stalled on 29 copies for nearly two years.

Some time in late summer 1988 I received a sales statement from our record distributors. My band’s first album, Let’s Get Away From It All, had come out a few weeks earlier, and I was dreading a similar fate to the debut single which had stalled on 29 copies for nearly two years.

I opened the envelope and stared at its contents for several minutes. We’d sold nearly 1,000 copies in the first couple of months. How? We hadn’t advertised it, so who in the UK even knew about it? Which part of the country had developed a sudden and urgent taste for the music of Friends? The answers were quickly revealed as ‘no-one’ and ‘none’.

In a fit of curiosity I phoned Red Rhino and spoke to one of the sales team. I asked where all these records had gone, and wouldn’t we now need to press some more? ‘Mostly Japan’, he replied casually, and yes, we should, as quickly as possible.

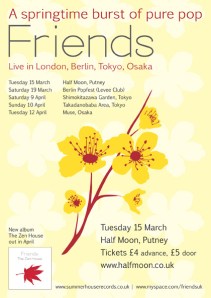

Since then Japan has been the place where our music has been most popular, the place from where we’ve received the most – and most enthusiastic – fanmail (now mainly email), where two other labels have licensed seven of our records, and where we’ve never managed to play. Until now.

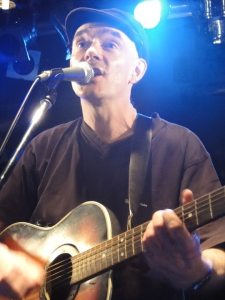

With the exception of a solo concert I played in Tokyo in 1995, our efforts to get ourselves transported to Japan for a few modest dates had proved fruitless. Late last year I was contacted by Tetsuya Nakatani, owner of one of the labels, Vinyl Japan, who have released our records there, asking whether we’d like to play three concerts with The Monochrome Set as an acoustic three-piece. After a bit of to-ing and fro-ing we agreed to go instead as an electric four-piece, and headed out to Tokyo in early April.

Apart from the concerts, the soundchecks, and the time hanging around the venues, the trip is a bit of a blur. But I made sure the musical part of it was etched on my mind as if it was going to be the last, and best, thing we ever did. I hope it’s not the last, but it was certainly the greatest experience of the band’s, and my, career. Even of my life.

Preparing and practising for the shows, my aim had been to deliver a set which made the same impression on the audience as concerts by Jonathan Kelly, The Chameleons, Steely Dan and a handful of others had made on me over the last 40 years. Something you look forward to as a fan, which fulfils all your hopes, and leaves you with a feeling on the night and in your mind afterwards that lasts for years.

For an experienced, tried and tested band who had been there before, maybe three shows in reasonable sized clubs wouldn’t be a big deal. For us they were a huge deal. Twice in the concerts I was suddenly hit by the enormity of what we were doing, and what it meant to be there, especially after a major earthquake, and was overcome by the emotion of it. Coming on to the stage in the dark at Shimokitazawa Garden, Tokyo, and seeing this packed sea of eager faces briefly choked me up in the first few lines of On A Day Like This. The culmination of 25 years’ waiting and hoping and preparing was suddenly too much. Singing while you’re crying might sound like a great idea in theory but actually just results in lousy singing, so I had to wrench back control of my voice and feelings. And introducing the last song at Muse Hall, Osaka, in our final night, again I cracked up, and only got through the slow introduction to You’ll Never See That Summertime Again thanks to the generous pauses built into the arrangement. Then the band came in, the song let rip and it was a joyous end to the tour.

We’d prepared an hour-long set, a mixture of old and new, with two songs from the new album The Zen House, and the balance of the set inclined towards the most familiar and popular records. We linked several of the songs to avoid too many mid-set pauses and chat, with intros to the next song emerging from the end of the previous one. It was a thrill to hear the ripple of familiarity as the start of old favourites like Far And Away emerged, and catching the eye of people in the audience singing the words with me.

We’d prepared an hour-long set, a mixture of old and new, with two songs from the new album The Zen House, and the balance of the set inclined towards the most familiar and popular records. We linked several of the songs to avoid too many mid-set pauses and chat, with intros to the next song emerging from the end of the previous one. It was a thrill to hear the ripple of familiarity as the start of old favourites like Far And Away emerged, and catching the eye of people in the audience singing the words with me.

So how was it for us? It’s impossible to judge from the stage, but I can safely say that it felt as though the three concerts were the best the band has played, and the best performances I’ve delivered. It’s been rare in our live career to be standing in front of a crowd that large and that enthusiastic, many of whom are there because they have known your music for years. After the first concert the promoter came up to me in the dressing room and said “William, come and meet your fans”. I’d been expecting to meet up with a couple of people I’ve got to know by email, but he meant something different. A queue of fans was lined up, armed with records and CDs, usually in immaculate condition, felt-tip pens and their names written on the back of their hands. Again, maybe routine for a bigger band than us, but for me moving, novel, flattering, and a rare chance to meet some of the people who have kept us going over the years.

The best advice I ever received about being in a band was ‘don’t split up’. Of course that’s exactly what bands should do when they feel their time’s up. But the advice came from someone who knew me, and knew that my music would keep coming as long as I had an outlet for it. I’m thankful for that advice, although I suspect we’d never have split up anyway. So what’s kept it going for 25 years, without knowing that a chance email would appear one day saying ‘how about Japan?’ A mixture of stubbornness, perversity, megalomania, faith in the music, quality control, a desire to connect with an audience, and the knowledge that there are people out there, an audience, to whom the music means something, even a great deal. And I’m more than ever convinced that most of those people live in Japan.

Two down, three to go. By now well and truly warmed up, we came back from Berlin a couple of weeks ago after playing the Popfest and started preparing for Japan.

Two down, three to go. By now well and truly warmed up, we came back from Berlin a couple of weeks ago after playing the Popfest and started preparing for Japan.

The warming up bit happened at the Half Moon, Putney, where the only heat was generated on stage as we played to two men and a dog, minus dog, minus also one of the men in the interests of gender equality, plus a woman and plus one of the other bands on the bill that evening. A small but perfectly formed audience, then. Our bass player, Edwin, however, was anything but warmed up, as he only just managed to stay awake and on his feet after a particularly virulent bout of what should be politely described as gastric trouble.

Berlin, on the other hand, was something else entirely. Right from being met at the airport we were beautifully looked after by our hosts Uwe, Olaf and Anja, and had plenty of spare time to explore the city before playing some time after midnight.

We made friends with fellow bands The Pooh Sticks (some fellow Welshmen for me to banter with) and the multitudinous Cola Jet Set (“they’re from Barcelona”), even randomly bumping into the latter troupe miles away the following morning and discovering more bizarre coincidences such as their familiarity with the streets of Walthamstow where we live. It is, indeed, a funny old world.

Our hour-long set, complete with acoustic interlude, seemed to go down well (although it’s always impossible to tell truly from the stage), and my use of exclusively German to introduce the songs didn’t appear to perplex anyone in the audience. Getting to bed at five in the morning is something I can only handle now if I’m getting up late the following afternoon, which wasn’t the case by several hours. But that’s pop ‘n’ roll.

And then it’s the comedown. Back to London, back to work, back onto the bike after the taxis and planes, and back into the routine.

Usually there’s nothing on the live horizon to look forward to, but this is the closest we’ve ever come to a ‘proper’ tour and the prospect of three more shows means that the feeling of wanting to do it again as soon as it’s over can be prolonged by another couple of weeks.

One more rehearsal to keep the set fresh in our minds and hands, and we should be ready to go. We’re off to Tokyo on Wednesday. In the words of the song, This Is The Start.