My blog has been going since July 2010, with a mix of pieces about music, following a lower-division football team (Mansfield Town), travelling on London Underground, and one (so far) customer service nightmare. A few years ago I moved to Turin and the blog went a bit quiet. I’ve now reactivated it, as I’ve got some new things to write about, including following a Serie A football team (Torino) and travelling on the Turin Underground.

If you’ve been reading, thank you, especially if you’ve commented either on or off the blog. And if you’ve been waiting for some new pieces, sorry about the slight delay.

So that’s the plan, and it will keep going for as long as I’m enjoying it!

There are few more aesthetically pleasing objects than the London Underground brand. The simply perfect, and perfectly simple logo, created in an age when logos didn’t really exist. The beautiful typeface on all the station names and Underground signs. The wonderful topographical map, which invites me on a speculative journey every time I look at it – the only drawback of all the extra mobility offered by the ever-growing array of new lines is that they spoil the delicious nostalgia of the original diagram. The station names, evocative of wartime conditions or Swinging London – pick an era of your choice. The thing is, such a triumph of branding should be followed up by a brilliant customer experience. It’s not. Somehow this doesn’t matter. I love the look, I tolerate the actuality. Please don’t let them change it. You see, I used to like those BBC balloons as well …

There are few more aesthetically pleasing objects than the London Underground brand. The simply perfect, and perfectly simple logo, created in an age when logos didn’t really exist. The beautiful typeface on all the station names and Underground signs. The wonderful topographical map, which invites me on a speculative journey every time I look at it – the only drawback of all the extra mobility offered by the ever-growing array of new lines is that they spoil the delicious nostalgia of the original diagram. The station names, evocative of wartime conditions or Swinging London – pick an era of your choice. The thing is, such a triumph of branding should be followed up by a brilliant customer experience. It’s not. Somehow this doesn’t matter. I love the look, I tolerate the actuality. Please don’t let them change it. You see, I used to like those BBC balloons as well …

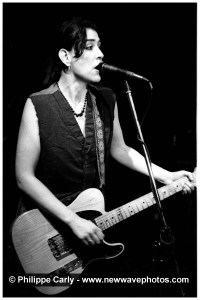

I wrote this piece as the introduction to the booklet for Whirlpool Guest House’s Rough Digs CD, a compilation of their single, album and four previously unreleased songs. Most of the world hasn’t yet bought the CD, and I thought their music merited a wider audience. True, most of the world also doesn’t yet read this blog, but add the two together and we’re getting somewhere.

Stockton-on-Tees in the mid to late 1980s was a hotbed of musical activity. Walk down the high street – allegedly the country’s widest – and within a couple of minutes you’d bump into several of the mainstays of the local band ‘scene’ – personnel who would often crop up in each other’s line-ups when not starring in their own. Every week the town’s Dovecot Arts Centre unveiled the newest, uppest-and-comingest indie phenomenon as well as showcasing the cream of the local talent, of which there was plenty. If you liked – or especially played – music, it was the place to be.

Stockton-on-Tees in the mid to late 1980s was a hotbed of musical activity. Walk down the high street – allegedly the country’s widest – and within a couple of minutes you’d bump into several of the mainstays of the local band ‘scene’ – personnel who would often crop up in each other’s line-ups when not starring in their own. Every week the town’s Dovecot Arts Centre unveiled the newest, uppest-and-comingest indie phenomenon as well as showcasing the cream of the local talent, of which there was plenty. If you liked – or especially played – music, it was the place to be.

On these sturdy foundations Whirlpool Guest House was built. Formed in disillusion by singer/songwriter Carl Green, it was a last-gasp attempt to break free from the shackles of futile touring – of playing the same set over and over in sparsely populated pubs and clubs, chasing ever-diminishing returns and ever-receding record deals (and indeed hairlines). Green had had some success with power-pop combo Carl Green and the Scene who had morphed into Rules of Croquet, but frustration had set in, and he hit on the novel idea of making music for fun again: a band that needn’t even exist in live form.

Roping in ex-Scene and Croquet cohort Andrew Davis on bass and Davis’ wife Sallyann, who had discovered an unexpected talent for ethereal vocals and spicy harmonies, the band set to work. Soon they had an embryonic single and album ready. One of the bonuses of recording at Graeme Robinson’s GDR Studios, Darlington, was that you got a top drummer, GDR himself, thrown in as part of the package. Robinson’s massive drum sound, mixed well to the fore, gave the band a harder edge and fuller feel than their modest line-up suggested.

Whirlpool Guest House was to be a minimal, anti-music-business set-up, whose live performances would be home-made Super 8 films projected to tapes of their songs and interspersed with zany introductions and wacky comments. Singer Green handled projection duties rather than fronting the band, and the rest of the group were on hand to sign autographs. In the late 80s this was hardly the classic template for promoting your music, but nearly 20 years later Green was able to bring his original vision to fruition with cartoon band The Close-Ups, created specifically for an internet age.

When not directing Whirlpool Guest House, Green was earning a crust as a print distributor, photographer, poster designer and mobile disco proprietor – a veritable jack-of-all-trades, a career choice celebrated in the song of that name, and in others. The songs don’t mess about and come straight from the heart – a risky strategy which sometimes reveals naivety and an occasional awkwardness, whilst more often hitting the emotional bullseye. A mix of the heartfelt and the quirky, the subject matter bypasses the standard boy-fails-to-meet-girl fare of fey indiepopdom, covering instead a diverse range of topics from hairdressing to random violence, ageing to abandoned infants. Much of the scenery will be recognisable to anyone who knows Cleveland, north east England.

The 1987 single The Changing Face, 1989 album Pictures On The Pavement and four unreleased songs are all that Whirlpool Guest House left behind, although as Shandy Wildtyme the same people, now playing live too, released an album, Luminous, in 1995. The last four songs on Rough Digs were always meant to make a CD single, but somehow it never quite happened. Then the band’s lifespan was up, and Green quit to form Gaberdine and latterly The Close-Ups.

We released this album to make Whirlpool Guest House’s music available to an audience who missed it first time round – usually by virtue of being unborn at the time. And also for those who did get it on vinyl but whose turntables have long since stopped spinning. Great songs, a cherished place, memorable days – Rough Digs is the record of a special time for the people who made the music, and for many who enjoyed it. For me it’s also the testament of an artistic collaboration and personal friendship which has lasted, on and off, for 25 years.

Welcome to the Guest House…and enjoy your stay.

PS Thanks to Graeme Robinson for finding the tapes, and to John Spence for getting the bastards to play.

![underground1[1]](https://fromthesummerhouse.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/underground11.jpg?w=497) Call me old-fashioned, but I like things like they used to be. As a small boy travelling on the tube in the sixties, I recall that unannounced stops of indeterminate length between stations would be unusual. Now they are the norm and travellers don’t even glance up from their papers to look confused. They take it as read. An explanation is the exception today. I also have no recollection of people arming themselves with bottles of water for journeys of perhaps a couple of stops on entirely temperate days, where no excursion into desert terrain was involved. Today there are even notices positively advising the carrying of potable water, and not only during high summer. Back then people didn’t die of dehydration on the tube. Or at least you never heard about it.

Call me old-fashioned, but I like things like they used to be. As a small boy travelling on the tube in the sixties, I recall that unannounced stops of indeterminate length between stations would be unusual. Now they are the norm and travellers don’t even glance up from their papers to look confused. They take it as read. An explanation is the exception today. I also have no recollection of people arming themselves with bottles of water for journeys of perhaps a couple of stops on entirely temperate days, where no excursion into desert terrain was involved. Today there are even notices positively advising the carrying of potable water, and not only during high summer. Back then people didn’t die of dehydration on the tube. Or at least you never heard about it.

Maintaining a long-distance relationship can be a challenge. Or, as we used to say in the days before the language of positive thinking, a pain in the arse. You start with the finest intentions. We’ll take turns to visit on alternate weekends. Actually, make that long weekends, as I can get away on Friday late afternoon, maybe catch the very early train back on Monday morning and still make it in time for work. Time being so precious, we’ll maximise every moment and make much more of it than we do right now. Think about it, that’s (part of) four days each week that we’ll be together – better than now – so it’s a potential upgrade in both quantity and quality. Of course, neither of you minds the other hanging around with exciting new people and doing the kind of things you do as a couple, as we’re both mature and it’s NO THREAT. And there’s always the phone and email, of course.

Maintaining a long-distance relationship can be a challenge. Or, as we used to say in the days before the language of positive thinking, a pain in the arse. You start with the finest intentions. We’ll take turns to visit on alternate weekends. Actually, make that long weekends, as I can get away on Friday late afternoon, maybe catch the very early train back on Monday morning and still make it in time for work. Time being so precious, we’ll maximise every moment and make much more of it than we do right now. Think about it, that’s (part of) four days each week that we’ll be together – better than now – so it’s a potential upgrade in both quantity and quality. Of course, neither of you minds the other hanging around with exciting new people and doing the kind of things you do as a couple, as we’re both mature and it’s NO THREAT. And there’s always the phone and email, of course.

And that’s fine – for a while. After that while, it’s less fine. Work’s really heavy this week – actually for the next couple of weeks – and I really don’t think I can get away for the weekend. Can we miss the next two, in fact? The next two turns into the next few, and before you know it, “I’ve actually been spending quite a lot of time with x” (where x = some loser who’s previously been casually dropped into the conversation in a wholly innocent way, but has now moved up from being NO THREAT to a REAL AND PRESENT DANGER). “And we get on really well together.” Then it’s “I think we could both do with some time apart and see how we feel about things.” Then it’s the showdown, the long goodbye (actually, can we make this quick?), the mature parting of the ways. Followed by the recriminations. The other person just “didn’t work hard enough at it”.

In the late 1990s I left Nottinghamshire after nearly a decade there, and moved back to live in London for the first time in 17 years. It was a big change, exciting but a wrench, mainly because it meant severing my ties with Mansfield Town.

But hang on. It’s only a couple of hours up the M1 for Saturday home games, and when you think about it, most of the away games are in the southern half of the country this season. London’s a doddle – there’s Barnet, Brentford and Leyton Orient to look forward to and, not much further afield, Gillingham, Wycombe, Cambridge. So away travel will actually become easier. OK, Torquay’s a trek, but easier from London than from Notts. Yes, I’ll have to forgo the odd midweek home match, but I can always take a day’s holiday if it’s a really crucial one. All things told, I’ll probably only miss about ten games a season. And there’s always the phone and email, of course.

That’s how it started off. And yes, it was indeed fine. Then, on a monochrome, London autumn Saturday, as grey as the 1950s, I had one of those across-the-crowded-room-at-a-party moments. Stags were playing at Leyton Orient, and climbing the steps up to the away-end terracing I anticipated, as a connoisseur of lower-division football grounds, being confronted by the usual ramshackle melange of construction works, hoardings and embryonic flats or car parks. As I reached the modest summit I stopped, looked, and let out the footballing equivalent of ‘phwooar’. Probably ‘phwooar’ itself, actually. The ground was gorgeous. Four perfect, un-redeveloped sides, two facing stands, two matching terraces, surrounded by a grid of closely-packed houses. My mind quickly got to work populating the empty space with crowds of post-war men in cloth caps, clutching their twopenny programmes, wearing rosettes and waving rattles. Jaw-droppingly beautiful, unlike Field Mill, which seemed to be in a permanent state of almost being rebuilt. I could move in here, quite easily.

When I thought about it, Leyton Orient and I went back a long way. We had friends in common. First there was Mr Grew. As a pupil at Barrow Hill Junior Mixed School in north west London, I had been aware that little clubs theoretically had fans, because I could see the attendance figures in the sports pages of the Sunday papers. But these weren’t necessarily real people. My friends and I didn’t know anyone who failed to support a proper club. We followed Chelsea, Tottenham, Arsenal. I was West Ham back then, in the days of Moore, Hurst and Peters. But Mr Grew, a teacher, claimed to support Leyton Orient, an attachment he always admitted with an embarrassed smile, a shrug and an over-acted confessional whisper. Mr Grew’s other distinguishing feature was that he sported extremely baggy trousers with turn-ups. By the mid-1960s it was 30 years since these had been fashionable and another 30 before they were to become so again. So the O’s did have supporters, albeit people who had missed their sartorial moment by two equidistant thirds of a century. Teachers generally didn’t have first names in those days but I think his might secretly have been Peter.

(In support of my thesis, my own class teacher, Mr Perkins, who had taught me, by then, most of what I usefully know now, was a Spurs man. He coached the school team and advocated the ‘push-and-run’ methodology of Arthur Rowe’s 1950s sides which were still fresh in his memory. Ambitious really, when his squad of ten-year-olds were more interested in keep-and-shoot. I once heard someone call him Bill.)

And then, of course, several players had turned out for both clubs during my time as a Stagsman. There was the bug-eyed crazyman Stuart Hicks, always eager to place his head in zones of maximum danger. There was Wayne Corden, dubbed, in one of those many football nicknames that don’t quite work, Cordinho, for his quasi-Brazilian ability at set pieces. Well, his quasi-ex-Port Vale ability, anyway. Not forgetting Mark Peters, who always seemed about to suffer, or to be recovering from, a broken leg or two. And there was Iyseden Christie, a representative of that footballing genre known as mavericks. Maverick status is usually conferred on big drinkers who won’t be told what to do on a football pitch, but Christie always struck me as a quiet, thoughtful man, who was blessed with unusual skill and trickery and an equally special ability to fall over. I believe he inspired the same kind of devotion amongst O’s fans as he did in his Stags days.

Thinking about it further, Leyton’s just down the road from my new home – with a following wind, 15 minutes on the 93 bus. We’re even in the same borough. Exploring the streets around the ground, I had noticed a sign in an estate agent’s window proudly boasting that their business was ‘protecting Leyton from the fear of unsold property’. That sounded like a fairly serious phobia for anyone in E10 to have developed, and I was thankful not to be suffering the same terror in neighbouring Walthamstow. Still, it was reassuring to know that some right-minded citizen, in however small a way, was fulfilling those supervisory duties and giving a whole community peace of mind and a good night’s sleep. Phew!

So, Leyton Orient. You and me, eh? It needn’t mean anything. I wouldn’t actually care about them. No-one need know. Just a casual fling which would keep me busy on a Saturday afternoon. Harmless, surely. And tempting. So tempting, in fact, that I started searching for reasons not to get involved, and save myself from a lifetime of guilt and regret. I found a few. For a start, could I live with that matchday announcer?

Leyton Orient’s PA wordsmith was surely in the top five most irritating practitioners of his craft. Not unusually, the name of the scorer of an away-team goal would be muttered under the breath like a curse. But a home goal was greeted by a routine which actually relieved the announcer of doing anything more than pushing a button. The recorded message that was broadcast to the ground, to the surrounding streets and for miles beyond was ‘Gooooooooooaaaaaaaaaaaaalllllllllll!’ Only much, much longer. Lasting what seemed to be several minutes, its enunciation might outlive even the restart by the away team. Initially provoking a wry smile, the ‘goal’ word pushed tolerance very quickly towards annoyance and finally to fury amongst the travelling support who would eventually turn, illogically, to the nearest loudspeaker and swear volubly at it. Fuck off indeed.

I had a hunch that the same employee was responsible for the selection of the ‘It’s A Knockout’ theme for the teams to run out to – a bit like some underachieving indie band choosing an irritatingly quirky retro TV tune with which to take the stage. I remember the programme well from the 1960s, mainly because watching it was the first time I recall experiencing embarrassment on someone else’s behalf (the programme-makers, not the plucky participants).

And I had to admit that when I looked again at my new love interest’s clothes there was something not quite right – red and white checks, like some kind of yuppie chess board, presumably to imply equal footballing status with the Croatian national team (or whoever it was whose shirt they’d copied) and to lend a cosmopolitan touch to the club in keeping with the vibrant cultural mix ‘on the street’.

But what really did it for me was an incident outside the ground a season or two later, an Alan Partridge moment born straight out of Spinal Tap, if that’s not too much of a genealogical stretch of the imagination. I was waiting for a friend, an O’s supporter, who in the end never turned up (he later flannelled that Chelsea had an equal hold on his affections anyway). It was a couple of minutes before 3 o’clock and I was about to cut my losses, write off my alleged mate and take my seat in the stand when a limousine pulled up outside a wide-open gate leading, via a tunnel, straight onto the pitch. Out stepped a short, scruffy, grey-haired man who shuffled down the dingy passageway to the half-way line, waved in desultory fashion and was greeted by a lukewarm round of applause. He (for it could have been no-one else) was announced (yes, by that man) as George Best. Even if they’d paid for nothing else, Leyton Orient had clearly laid on a posh car to allow the thirsty Irishman to raise his hand for a few seconds and then take his seat in the not particularly VIP area. Astonishing. Gratifyingly, the club, and especially the announcer, must surely have been crapping themselves silly that George Best would do a ‘George Best’ and join my friend in the ranks of the no-shows, having presumably been advertised as a matchday attraction. I justified my now rapidly-cooling ardour by rationalising that this was no way to manage a celebrity appearance, let alone a football club.

Taking an uncharacteristically logical approach to my complicated love tangle, I decided it was time to draw up an emotional balance sheet. When the accountants packed up and moved out I was relieved to see that Mansfield Town, by doing nothing much at all, emerged on the assets side, while Leyton Orient, offenders against several behavioural norms, were listed as a clear liability. That was that, then.

Next time I went back to Brisbane Road the away end I’d admired a few years before was gone for redevelopment. It was no longer there. Flats, apparently.

So, Mansfield Town. You and me, eh? My dalliance was never actually consummated, or more truthfully should I say I withdrew at the last moment? Either way, I didn’t inhale. Yes, there’s always the phone. And I must get round to sending that email. Wonder if they’ll have me back.

I wasn’t actually there. Half an hour early, one station away, I suppose I could have claimed some kind of spurious proximity to the bomb and manufactured an over-dramatic ‘lucky escape’ boast. But I’ve been travelling over the ground for a couple of weeks now, so I was even one whole mode of transport removed from danger. I checked on the people I care about and watched it all on TV. The next day my thoughts turned inward. Someone I love who doesn’t know it. Someone I miss who I never told. Someone whose pride and mine stopped us talking years ago. Someone I tolerate but would rather not. What if? What if them as well? This should change everything. Can I make it different? I don’t know. I will try.

I wasn’t actually there. Half an hour early, one station away, I suppose I could have claimed some kind of spurious proximity to the bomb and manufactured an over-dramatic ‘lucky escape’ boast. But I’ve been travelling over the ground for a couple of weeks now, so I was even one whole mode of transport removed from danger. I checked on the people I care about and watched it all on TV. The next day my thoughts turned inward. Someone I love who doesn’t know it. Someone I miss who I never told. Someone whose pride and mine stopped us talking years ago. Someone I tolerate but would rather not. What if? What if them as well? This should change everything. Can I make it different? I don’t know. I will try.

I used to love cycling. As a student, and after, in London from 1977 to 1982 I cycled everywhere. It was a moneysaver, a sightseeing opportunity, and a spiritual liberator. After a few bad experiences I stripped my bike of anything inessential to make it unworthy of theft. It finally consisted of a frame, two wheels and a chain and, usually, me.

I used to love cycling. As a student, and after, in London from 1977 to 1982 I cycled everywhere. It was a moneysaver, a sightseeing opportunity, and a spiritual liberator. After a few bad experiences I stripped my bike of anything inessential to make it unworthy of theft. It finally consisted of a frame, two wheels and a chain and, usually, me.

Of several epic journeys, my greatest pride was a marathon from Greenwich to Twickenham to see my friend Brian Willoughby play his guitar in a pub. The landlord was sufficiently impressed with my dedication to let me in free. The band, possibly displaying an underdeveloped sense of self-esteem, were simply incredulous that anyone would pedal that far to see them perform. In truth, I’d only gone to see Brian, whom I liked and admired, and who later sold me the beautiful Gibson guitar he played that night.

When the time came to look for work, my embryonic CV, in the absence of any real jobs to quote, placed its emphasis on education, work experience and ‘other interests’. This final section signed off with the nicely pretentious bullet point ‘exploring London by bicycle’, a line which survived my editorial knife for much longer than it should. When I left London my bike owed me nothing and I gave it away.

Where I had gone, a bicycle was uncalled for. But later, in the early 1990s, living in rural Nottinghamshire, I bought a new machine and substituted ‘exploring London’ with ‘discovering the countryside’ (although not on my rather more substantial CV). Around 1995 I suddenly noticed a changing trend in cycle custodianship. Where once people had parked their bike against a wall or chained it to a lamppost, now the fashion was to lay it out on the pavement, usually directly outside the shop the owner was visiting (or burgling). To me this seemed to invite passers-by, especially myself, to walk over, rather than round, the bike, but I took it to be a new sign of ‘coolness’, along with needlessly spacious trousers and a tendency to call people ‘man’.

Returning to London in 1999 I considered cycling again but ruled it out on grounds of sweat, danger, middle age and frustration. Now the new trend was cycling on the pavement. Not just randomly, occasionally, but as the general choice of thoroughfare, newly commandeered for two wheels. I resented sharing valuable pavement space with cyclists and started to challenge them, formulating reproaches that combined vigorous insult with expressions of disapproval at their dual qualities of selfishness and cowardice. Given the time constraints in which to deliver my choice observations, I would keep my sentences short, usually limiting them to two words, an adjective and a noun. Not actually sentences at all, then. Again, because brevity was essential, the noun usually consisted of a single syllable.

Walking down Clater Street, east London one day, a cyclist missed taking off the entire left side of my body by a mere couple of inches. Avoiding the temptation to exaggerate for effect, I conservatively estimate his speed at 20 mph (your honour) as I swerved out of his path. Even more annoyingly, he was singing as he flashed past. I turned and shouted the rudest from my repertoire of insults. Facing forwards again I noticed that a police car had silently pulled up alongside me, its window winding down and the long arm of the law beckoning me over.

Guessing that one or both occupants had seen the incident, and that it was fresh in their memory, I anticipated, if not congratulation, then at least an enquiry as to my wellbeing after such a narrow escape. On the contrary, the speaking policeman’s first comment was a reprimand on my vocabulary in a public place. His second was to advise me not to try to take the law into my own hands. Hands which were now a whole street away from those of the rapidly disappearing cyclist.

I countered that, rather than upbraiding me on my language, he might be doing something about the phenomenon of pavement cycling, a pastime which might seriously damage someone less nimble than myself. Nodding sagely, Bad Cop assured me that they were ‘onto it’, but that I should watch my behaviour ‘on the street’. I might be committing a public order offence. Reckoning it unwise to engage in further healthy debate with the law, I used open-mouthed silence to convey my doubt that sitting pointing the wrong way in a stationary car represented any genuine attempt to curb this burgeoning crimewave. But when I asked politely why I should desist from offering helpful advice to errant cyclists, the answer was clear and graphic. They might stop and knife me – ‘or something’.

Ah. So there we are. As Good Cop might have reported: to sum up, m’lud, my colleague proceeded in an orderly manner to advise accused confrontational pedestrian to avoid risking a stabbing by having it out with public pests and lawbreakers. Or something.

I could rant like a vox pop about the police wasting their time with the likes of me instead of catching real criminals. I even briefly considered vowing to clean up the streets, finding the nearest mirror and asking it: “You talkin’ to me? You talkin’ to me? You talkin’ to me? Then who the hell else are you talkin’ to? You talkin’ to me? Well I’m the only one here. Who the fuck do you think you’re talking to?” (Answers to questions 1, 2, 3 and 5: Yes. Answer to question 4: Obviously, no-one. Answer to question 6: You, exclusively.)

But really I’m thankful still to be at liberty, grateful to Good and Bad Cop that there’s no place on the streets for dangerous vigilantes and that there is someone like them around to protect people like me from people like myself.

They put up signs at the top of the escalators to tell me how they’re doing. This one is dated today, 5.30 this morning. It is now 6.37am. Anything worth knowing is written in type so small that a calculation is involved, to balance the time invested in trying to read it against the value the message will deliver. The notice alerts me to an inconsistency: how is a ‘good service’ different from a ‘normal service’? Both are offered on the same sign. Very suspicious. Have I caught out London Underground Ltd here? Are they admitting that a ‘normal’ service is not ‘good’ and would this thesis stand up in a court of law? Either way, I have won a small but definite victory.

They put up signs at the top of the escalators to tell me how they’re doing. This one is dated today, 5.30 this morning. It is now 6.37am. Anything worth knowing is written in type so small that a calculation is involved, to balance the time invested in trying to read it against the value the message will deliver. The notice alerts me to an inconsistency: how is a ‘good service’ different from a ‘normal service’? Both are offered on the same sign. Very suspicious. Have I caught out London Underground Ltd here? Are they admitting that a ‘normal’ service is not ‘good’ and would this thesis stand up in a court of law? Either way, I have won a small but definite victory.

As a teenager growing up in Chester in the early 1970s, you identified yourself by the bands you followed along with the football team you supported. The albums you carried under your arm to school or pulled out of plastic carrier bags to show off or exchange in the yard at break time said as much about you as the length of your hair or width of your flares. There were clans dedicated to the unspeakably pretentious (Yes, Pink Floyd, Genesis), to the teenyboppingly trivial (Slade, T Rex, Osmonds even) and to the interesting left-field ‘alternatives’ – people like the Incredible String Band, King Crimson and Strawbs. My own circle of friends were big Strawbs fans, and had followed their progress all the way from acoustic trio to full-on rock group. By 1971 they had released four albums, and records like From The Witchwood and Just A Collection Of Antiques And Curios were rarely off our turntables.

As a teenager growing up in Chester in the early 1970s, you identified yourself by the bands you followed along with the football team you supported. The albums you carried under your arm to school or pulled out of plastic carrier bags to show off or exchange in the yard at break time said as much about you as the length of your hair or width of your flares. There were clans dedicated to the unspeakably pretentious (Yes, Pink Floyd, Genesis), to the teenyboppingly trivial (Slade, T Rex, Osmonds even) and to the interesting left-field ‘alternatives’ – people like the Incredible String Band, King Crimson and Strawbs. My own circle of friends were big Strawbs fans, and had followed their progress all the way from acoustic trio to full-on rock group. By 1971 they had released four albums, and records like From The Witchwood and Just A Collection Of Antiques And Curios were rarely off our turntables.

The new LP would be the one to push them finally into the big league, leading eventually to chart positions and Top Of The Pops. The tour to promote Grave New World brought Strawbs to Manchester, and five of us set out by train early on the evening of Saturday 12 February 1972 to see them at the Free Trade Hall. Expecting to miss the last train back, someone’s mother or father would collect us after the show.

We arrived early for the headliners, but slightly late for the first support act. On stage was a man in a black polo neck sweater, with a shaggy mane of black hair and a beard. He looked like a star and sounded amazing, the chords that rang out of his acoustic guitar conjuring up a whole rhythm section. Hurrying to my seat so as not to miss any more, I flipped through the tour programme and learned that this was Jonathan Kelly, singer-songwriter, and that he too had just got a new album out.

The standard format for song introductions back then was incomprehensible mumbling (thisisasongabout…mmmggghnnnggghbwaaahhh…hopeyoulikeit) punctuated by copious bouts of guitar tuning – a downbeat style straight from the Bob Harris School of Public Presentation. Jonathan Kelly was the antidote to this approach. His between-songs patter was rattled through breathlessly at breakneck speed, with plenty of laughter and a surreal line in humour, all delivered in a warm, intimate Irish voice. I wondered what fuelled his astonishing energy, and reckoned it was simply adrenalin, the thrill of being there on stage, playing his music to a new audience and earning their devotion.

Singer-songwriters back then were ideal, low-maintenance support material for bigger acts – no shifting around bulky equipment or setting up second drum kits; just a quick one-two-check and you’re away. (The other support that night, a mime artist, made even fewer demands of the PA system.) That tour must have been a godsend to Jonathan Kelly – to be playing in proper concert halls and theatres to big audiences, all predisposed to like his music, and to be winning them over night after night. Like me, thousands of others became instant fans, and went from concert hall to bed to record shop the next day. I called in at Migrant Mouse, the local independent in Northgate Street on the way home from school the following Monday and bought Twice Around The Houses for about £2.

I’d somehow expected that the album would just be Jonathan Kelly and his guitar. After all, the songs had sounded just perfect played that way and I couldn’t imagine them needing any more. But the record featured some top musicians, the cream of the London session mafia back then. Names like Peter Wood, Tim Renwick or Rick Kemp might not mean a lot today, but these were the people you got in to add class to your record, enhance the music and colour in the spaces.

It’s a wonderful album, to this day one of my favourite few records, one I will never sell or give away, and I still get a thrill putting it on and settling down to listen. People I’ve been close to have pulled the record off the shelf, said “wow, who’s this?” and then, 45 minutes later wanted to play it over again, and again, and again.

Twice Around The Houses is a collection of ten songs covering everything you could wish to hear about. Songs of brotherhood and community (We Are The People and We’re All Right Till Then); of romantic yearning (Madeleine); of love and loss (Leave Them Go and the achingly, unbearably beautiful I Used To Know You); cautionary tales like the folkish, allegorical Ballad Of Cursed Anna and its contemporary counterpart Hyde Park Angels; songs of home (Sligo Fair and Rainy Town, surely a paean to the singer’s origins in Drogheda); the Dylanesque stream-of-consciousness of The Train Song; and finally a lullaby of exhausted contentment, Rock You To Sleep. Songs of everything, really. It’s an album where practically every track is a standout, if that’s possible – with wonderfully crafted, articulate lyrics, beautiful chord sequences, and memorable, uplifting melodies.

All these songs are favourites, but most of all I love Sligo Fair, the tale of a girl who longs to escape her humdrum rural life and hitch a ride to the big city with the travelling fair people. Just three verses and the picture is painted and the simple story told, with this closing image:

Way above the northern coast the seagulls circle high

As to the west the sinking sun spills gold across the sky

And homeward wend the Friesian herd to the ending of their day

And Sligo Fair is just a week away

I could quote line after magnificent line of Jonathan Kelly’s lyrics. But the best service I could do him – and you – is to mention the two-CD set of his pair of solo albums for RCA, where you’ll find the words surrounded by his gorgeous music.

The cover of Twice Around The Houses is one of those simple, evocative 70s classics that you don’t see so often in these days of antiseptic graphic design. It’s a photograph of the singer, probably in London, possibly in the rush-hour, at dusk, as he waits to cross a road. Wrapped up, with a scarf round his neck and the old-style Guardian sticking out of a coat pocket, his eyes focused on something miles away, it’s the picture of one man in a crowd of millions trying to get by and stay ahead in London – like the character in Rock You To Sleep.

A year later came Wait Till They Change The Backdrop. The follow-up saw Jonathan Kelly stretching his musical muscle, with longer songs, more complex arrangements, greater variety of texture (even, amazingly, a steel band on I Wish I Could and some Queen-like vocal harmonies on the title track) and a slightly darker mood overall. The album is a reminder that Jonathan Kelly was never really a folkie, more a musician whose natural milieu happened to be the folk club circuit – an acoustic rocker with a great pop sense, as the two albums he released with his own band as Jonathan Kelly’s Outside demonstrated later. There’s another memorable photo, this time a tableau of 21 people involved in the record – presumably, in those pre-photoshop days, all together in the same place at the same time. It’s a wonderful portrait of a kind of hippy extended family, with young and old, black and white, male and female, all manner of hairstyles – and at the centre a now clean-shaven Jonathan Kelly, looking proudly straight into the camera, surrounded by this huge cast of characters who have lent their talent to his music.

For the few years at the height of his musical career many people loved Jonathan Kelly, just as my friends and I had done that night in Manchester. I’ve only recently discovered the Benjamin Franklin quote: ‘If you would be loved, love and be lovable’. Jonathan Kelly was lovable in abundance, and audiences adored him as their own. There are stories of him going to a pub for a quiet drink and being reluctantly thrust onto the stage with a guitar and captivating an unsuspecting audience for the next hour. As well as the delightful character introducing the songs, there was that marvellous voice, sometimes vulnerable and tender, always sounding very close to the listener, but equally able to let rip and belt it out like a fully paid-up rock ‘n’ roller. In the booklet accompanying the CD set, Dave Stringer, who used to manage his folk club work, writes: “It was always a special pleasure to drive Jonathan to a new venue, where many of the crowd would not have seen him before. To feel the awe of the audience, to be lifted up with them, to share in their sheer pleasure, to be overwhelmed by the response at the end. To my knowledge, the magic never failed, no matter what the make-up or size of the audience”.

Then, some time in the mid 1970s, Jonathan Kelly disappeared off the face of the music scene. There were rumours that he’d become a recluse, even that he’d died. My own interests in music had moved on, but I still listened to his records just as keenly as ever, along with the punk and new wave I’d discovered. I often thought of him, wondered what he was doing, hoped he was OK, and would have loved the chance just to say to him ‘what happened to you?’

What happened was that he had dropped out of music altogether. From the engaging idealist, the Workers Revolutionary Party activist who used to sign autographs ‘Peace and love, Jonathan Kelly’, he had become a heavy drug user and a man who was rapidly leaving behind the people who cared about him. Finally he had grown disillusioned that his music couldn’t make the difference he wanted, couldn’t change the world any more than his politics had done, and thoroughly disillusioned with himself. In an interview many years later he describes the man he had somehow turned into, a person he no longer liked very much – arrogant, hypocritical, and self-indulgent. It’s a scathing and brutally honest appraisal, delivered entirely without the self-pity we expect in the age of the teary celebrity confessional.

But he had survived, was alive and well and had found another faith. Far away from that London rush-hour he had started a new life, a family and his own small business and was an active Jehovah’s Witness, giving his time to help people deal with their own problems. In the early 2000s a dedicated fan tracked him down, created a website about his life and work, and cajoled the first performances from him for nearly 30 years. Even after all this time there was a devoted following, people who, like me, remembered and loved his music, and relished the chance to experience it again.

The second career was short-lived, as he reckoned that the allure of music, the buzz of performing and recording again, would diminish his focus on the religious work, with his congregation, that mattered most to him. From a selfish point of view I was disappointed to be missing out on this ‘comeback’, having caught so little of him first time round. But Jonathan Kelly owes me nothing. I’ve taken all I wanted from his music over the years, and every day still I think of one or other of his songs…so whatever you choose, Jonathan, is absolutely fine by me.

Songwriters are often asked where their ideas come from – do they have to work hard for them, are they based on personal experience or imagination, which comes first, the music or the words? On the website dedicated to his work, there is this quote from Jonathan Kelly:

“I’ve got music in my mind everywhere I go. Songs come to visit and if I’m quick and copy them down before they leave, then I can play them to someone else. Many times they just come and stay a while and then slip out the back door never to be heard of again. It don’t worry me, it was just nice to have them around for a while.”

It’s the best description of artistic inspiration I’ve ever read – modest, even humble, easy to understand, and devoid of the mystique and pretension with which writers sometimes clothe their work.

Jonathan Kelly is one of a handful of people whose music means most to me. Great, great songs, which are in my mind, too, wherever I go, and keep on playing years after I first heard them. Music which shares my melancholy when I’m feeling low, lifts my spirits when I need a hand up, and smiles back at me when the sun’s shining. I’ve never met Jonathan Kelly, and only enjoyed his company for the length of that short set back in 1972. But I’m thankful that, just like the musical ideas that visit him, he dropped in on my life nearly 40 years ago and stayed long enough to share his songs with me before moving on somewhere else. Wherever he is, whatever he is doing, I’m sure he’s still illuminating people’s lives, and I hope that he too has found love and peace.

Leave the sailor to the seaway, leave the shepherd to the fold

Leave your loved one to her chosen and leave them go

Leave them go

They must have just come from some David Cassidy convention or fan club meeting. Festooned with memorabilia of the acned 70s heartthrob, several fortyish women are reliving some happy memories, and not just of this afternoon. Sitting opposite, but otherwise miles away, I’m replaying an unhappy conversation, exchange, encounter I’ve just finished. I smile involuntarily at something I said, while my radar picks up a nostalgic paean to tight trousers with wide flares from across the carriage. They think I’m listening. “He knows what I mean. Look, he knows. You know, don’t you?” My sadness, and the comfort of my daydream, hold me back from joining in their harmless banter. But now they’ve got me. I’m complicit, I’m hooked in. I spend the distance to the next stop lashing my features into a parade of forced smiles, shrugs, snorts and puffs of artificial laughter. Nothing against Cassidy. I just thought the tube was my refuge.

They must have just come from some David Cassidy convention or fan club meeting. Festooned with memorabilia of the acned 70s heartthrob, several fortyish women are reliving some happy memories, and not just of this afternoon. Sitting opposite, but otherwise miles away, I’m replaying an unhappy conversation, exchange, encounter I’ve just finished. I smile involuntarily at something I said, while my radar picks up a nostalgic paean to tight trousers with wide flares from across the carriage. They think I’m listening. “He knows what I mean. Look, he knows. You know, don’t you?” My sadness, and the comfort of my daydream, hold me back from joining in their harmless banter. But now they’ve got me. I’m complicit, I’m hooked in. I spend the distance to the next stop lashing my features into a parade of forced smiles, shrugs, snorts and puffs of artificial laughter. Nothing against Cassidy. I just thought the tube was my refuge.

With everyone’s commitment to great customer service these days it’s good to feel that the people who look after my money, energy supplies, telephone connection and all-round wellbeing have my best interests at heart.

With everyone’s commitment to great customer service these days it’s good to feel that the people who look after my money, energy supplies, telephone connection and all-round wellbeing have my best interests at heart.

I know this because I’m regularly told that my call is important to them (not quite important enough, though, to answer within the next 30 minutes), that they take my feedback seriously (and are far too polite to tell me exactly where to stick it), and that they are constantly trying to improve their service (but secretly like things just the way they are).

Generally I try to avoid dealing with the big corporations who control my happiness, and only do so when there is a problem I have to resolve – what they call an ‘issue’. This is because the amount of time and emotional energy I need to invest in dealing with my bank, utility companies and other monoliths far exceeds my available resources of either. I’ve pretty much resolved never to move house again because I know that if I do, BT will wreak such havoc for the next few weeks that I will either die in the process or never have the means to work again.

All of these companies are bad (and not ‘as in good’), but those whose business is based on the internet are worst. It’s as if they believed that simply being an internet facility was in itself good customer service, removing as it does those whimsical humans who get in the way of consumer satisfaction. I’m generally suspicious of companies who bury phone numbers, email and postal addresses in the deepest recesses of their website and who view these perfectly serviceable tools of communication as last resorts when their automated responses fail, and I assume they do this in order to minimise contact with their foul-smelling clientele.

Here we name and shame the guilty men. Come on down National Westminster Bank, EDF Energy, last.fm (the record label side, anyway), Virgin Trains, Royal Mail (especially the PO Box division, but actually all of it), and Ebay. I despise you all. And an honourable mention for Tiscali (even though they’re not one of mine) with whom I spent an entire weekend locked in conflict as I tried to sort out my mother’s phone and broadband connection after she had made the fatal mistake of relocating from the ancestral home.

I can detect the early physical signs of gearing up to contact any of these companies (or ‘bastards’ as they are known in the industry jargon) – feelings of anxiety, irritation and a tendency to procrastinate. It’s not the anticipation of confrontation that produces these symptoms – I’m a frequent and vigorous complainer – nor the actual dealing with the suppliers, although that’s bad enough. It’s finding out how to get hold of them and locate a single person with whom to have a sensible conversation.

I learned the rules of engagement in these encounters long ago. Don’t swear, however mildly, however severely provoked. That only results in an immediate and dramatic swerve in the conversation, away from your ‘issue’ and towards the kind of language the customer service adviser isn’t paid to listen to. The furthest I go, in moments of extreme emotion, is to describe their company as ‘the absolute pits of customer service’. ‘Pits’ doesn’t feature in the long list of words their salary won’t cover – possibly because it was legitimised by John McEnroe back in 1981 and we’ve all heard it so often since then that it’s become safely sanitised. But it still sounds strong. Advisers are very sensitive, too, about the word ‘you’. So any statement beginning ‘last time I called, you told me…’ will be countered by the assertion that they themselves didn’t tell you that. Which leads down another by-way, to explain that ‘you’ are a representative of your company, like the last one I spoke to, who was presumably giving the company line rather than a personal opinion. I know it’s not only you who works there. They were called Joe, or Sue, or Adam and, like all customer service advisers, were born without a surname.

My most recent run-in was with Ebay, and therefore also with Paypal. If you go to them with an ‘issue’, Ebay’s particular forte is to repeat your question back to you in the hope of convincing you that their understanding the problem is the same as solving it. Then repeat it again. And again.

For reasons known only to Ebay, I was no longer able to list anything in the global auction house. I’ve only ever sold with them, never bought, as, having spent the first half of my life accumulating the generically-named ‘stuff’, I am dedicating the second half to getting rid of it – books, records, memorabilia I will never realistically look at or listen to again.

My account was restricted, and I only found out when trying to offload some 1973 copy of Melody Maker that it had ‘exceeded the limit’. This was interesting, as I’d never been told it had a limit, nor what such a limit might mean. Was there only a certain number of Ladybird natural history books I was allowed to flog to eager Australians who had somehow missed out on this wonderful resource? To have my account liberated again, I would have to provide Ebay with my credit card details. Also very interesting, as they’ve never had them before. I’ve always paid my fees to Ebay directly from a linked Paypal account, and would very much like this entirely satisfactory arrangement to continue. Fair play to Ebay, they are completely upfront in telling me they want these numbers specifically so that they can take their money from the card, in contravention of my wishes.

So here I go. It’s online to grapple with Ebay’s alleged help facility. As with most of these services, any query must have its essence crammed into one of the standard formats they offer – these are the questions most people ask us; if you’re not like most people, then too bad.

Inevitably my particular problem isn’t offered, so I choose the nearest equivalent, and next day I get a reply. The first line of defence is to tell me that the issue must be with Paypal who, predictably, have erected the same impenetrable walls of obfuscation. After going three rounds with both Paypal and Ebay, both of whom deny any awareness of any problem, or possible reason for the same, I am eventually directed to Ebay’s ‘live chat’. This looks promising – the chance of a rational question and answer session which should, surely, deliver a way out of my online hell.

Live chat is a misnomer. (A word of warning to those who like that kind of thing – there’s no heavy panting or ecstatic moaning. Although probably plenty of other kinds of moaning by customers with other kinds of frustrations). It’s not a chat, it’s an online corrrespondence, and doesn’t feel any more ‘live’ than any email transaction. The live chatperson starts by thanking me, of course, for my query, apologising for keeping me waiting, and asking me initially to outline my problem. The apology is a fairly regular recurrence from then on, as I spend the next half hour chained to my computer with frequent updates as I slowly move up from 39th place in the queue. When my ‘representative’ has finally beaten 38 desperate customers into submission, it’s my turn. I’ve outlined my problem, and the ensuing chat goes something like this.

- Ebay asks me to outline the problem (again).

- I outine the problem (again).

- Ebay affirms ‘so the problem is, Mr Jones, that your account is restricted, and you want to remove the restriction’.

- Yes, that’s the problem I outlined, got it in one.

- OK, we understand that your account is restricted, and you want to remove the restriction. And is your query specifically about this issue?

- Yes, not just specifically, but also generally, vaguely, every way you can think of.

- Thank you Mr Jones, if your problem is that your account is restricted and you want to remove the restriction, I will need to ask you some questions to see if we can resolve this situation.

- Good, expected that, now we’re getting somewhere.

- Several questions later, and it’s back to blaming Paypal.

- No, no, no, they’ve said it’s nothing to do with my Paypal account, they’ve referred me back to you.

- Mr Jones, I have to ask you to go to our Help page; when you receive our email response, click the link and one of my colleagues will be able to help you.

This fruitless chat has taken about 40 minutes. I endure this ritual twice more. The third time I do the outlining, waiting, reading apologies, repeat outlining, only to be told, 30 minutes later, that I have come to the wrong place entirely and need to follow this link to go through the process again. Right. Give up.

I suddenly notice that my last email from the Pal Of Pay concludes with the words ‘Kindly note: try this number’ followed by an apparently valid, relevant, genuine-looking 0845 phone number. Yes, that’s very kindly.

I ring the number and spend 20 minutes on hold. Eventually something stirs at the other end of the line. The voice is a strange synthesis of Professor Stephen Hawking’s cosmic tones and the kind of stateless mid-Atlantic drawl that international golfers and tennis players acquire, and sounds as if it’s coming from a chamber at or near the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. I reckon that the voice does, just about, represent a real person, and decide to persevere. It identifies itself, improbably, as Brian.

Like the live chat, Brian has been programmed to repeat my question and his answer until, weeping with frustration, I go off and find something hard to kick. I eventually tell Brian that he isn’t helping me at all and that I’d like to speak to his supervisor who, presumably sharing the underwater lock-up, takes me through the same elaborate dance of outlining, questions, apology, repetition. And then finally, amazingly, she helps me. My account was restricted because Paypal were late paying Ebay my last monthly fees (I later discover that the reason for this lies with my bank cancelling a direct debit to Paypal without telling me). I need to reset Paypal as my preferred payment method and the problem will be solved. This takes me a couple of minutes. Any of these advisers, chatters, Brians could have told me this, if they had only treated me as an individual rather than an issue.

One week on, after 35 minutes on the phone, 12 emails to Ebay and Paypal, and three sessions of live chat totalling about 90 minutes, my issue is resolved, and I can once more put my Robert De Niro videos up for auction for anyone who still has the means to play them.

Thank you for your interest. Is there anything else I can help you with today?

It’s the purest form of fundraising you could imagine. No charity pen, no £2 to save some starving African village, no sponsorship forms, just a torn polystyrene cup and the (presumably) good cause is standing right in front of me making a case for his next cup of tea or a night in the hostel. Here’s the routine. Always: the over-apologetic intro. Sometimes: the pompous advice returned about getting a job. Occasionally: the child in tow. Rarely: an actual gift of money. Never: any individual talk or eye-contact with the audience. What could make it work better? Possibly nothing. In the absence of any evidence that we can make a difference, it’s a test of trust. But I’d lose the guitar. And the dog.

It’s the purest form of fundraising you could imagine. No charity pen, no £2 to save some starving African village, no sponsorship forms, just a torn polystyrene cup and the (presumably) good cause is standing right in front of me making a case for his next cup of tea or a night in the hostel. Here’s the routine. Always: the over-apologetic intro. Sometimes: the pompous advice returned about getting a job. Occasionally: the child in tow. Rarely: an actual gift of money. Never: any individual talk or eye-contact with the audience. What could make it work better? Possibly nothing. In the absence of any evidence that we can make a difference, it’s a test of trust. But I’d lose the guitar. And the dog.

In his later years my father took to abusing the television screen when confronted by anything that especially provoked his ire. A man of strong and sometimes irrational loves and hates, he had taken a particular dislike to Dr David Owen, the suave and rather pompous former Foreign Secretary and leader of the short-lived Social Democratic Party. My father’s beef with Owen was that “you couldn’t trust him”, an accusation it was hard to verify in the absence of any clear behavioural evidence. (Having done his time as a politician, Owen was now generally seen on the box pontificating about other people’s work.) I heard this charge levelled with increasing vehemence every time the floppy-haired ex-medic’s talking head appearing on the TV set. Not a fan myself, I was nevertheless intrigued to learn what Owen had done to my father to inspire such intense antipathy. Eventually, backed into a corner and pressed on what was the giveaway sign of the unfortunate flaw in the doctor’s character, he puffed himself up to deliver the killer rationale, the ultimate justification for his slander. Laying down the trump card in his argument, he gestured to the screen and triumphantly announced, “Well…just look at his mouth”.

I could see his point. The gob in question was a thin lateral slot, almost devoid of lip content, and you might well choose not to entrust your car-keys – or indeed country – to its owner. Point made, argument won, my father reclined contentedly to enjoy the rest of the day’s news. I was left to reflect briefly on the faintly disturbing fact that he, a medical man himself, was still, in the early 1990s, espousing the barmy Elizabethan belief that you could divine a person’s character traits from their face.

As if to prove the maxim that we all turn into our father, I too have started shouting insults at my ancient television. Even when I’m on my own. Even in the absence of cats. Although not at David Owen, who is now well into actual and televisual retirement. The object of my abuse – unless Robert Peston’s face has popped up in front of me – is football. The whole paraphernalia of football, really, before, during and after actual games, apart from the few minutes of continuous play you see from time to time. (In the case of the BBC’s Economics Editor the obscenities reflect my astonishment that he is actually allowed and paid to talk on television, having clearly picked up the art of speech from a set of 1930s teach yourself Esperanto discs.)

Yes, everything about the beautiful game is an affront to my senses, especially its ugliness. Its essence has been distilled into a formalised sequence of visual clichés starting well before the magical hour of 3pm when, in anticipation of the maelstrom of cheating, play-acting, shirt-pulling and time-wasting to follow, we can enjoy the absurd hypocrisy of those choreographed hand-shaking line-ups. This is where players compete to look the most uninterested and show least ‘respect’ to the owners of the hands they fleetingly touch. In deference to the Premier League’s inflated sense of its own importance this sad simulacrum of some gentlemen’s code of honour precedes not only cup finals, but even the most routine sleepfest involving, say, Bolton and Wigan.

With the game now under way, appreciate the art of ‘shepherding the ball out of play’, where an opponent is wilfully obstructed by the dancing of some elaborate, jerky tango over the ball, and wonder at the fact that this tactic is never now penalised. And my sense of moral righteousness these days is outraged more by players ‘stealing yards’ at throw-ins than by the bonus any banker is paid. For God’s sake, man, it didn’t go out there, it went out back there!

But no, players really are sporting. Witness those sham uncontested drop balls and the round of applause the ritual always draws from the crowd, as if it’s just been devised and agreed by today’s participants as a token of fair play.

Match officials are never popular, and I actually don’t want to have to like them, so please spare me laughing referees and, in a particularly irritating subset of the genre, laughing referees running backwards with arms and legs exaggeratedly pumping. Completely unnecessary, and quite possibly a health and safety issue.

I can also happily live the rest of my life without any prepared goal celebrations at all but, paradoxically, equally despise players who ostentatiously refuse to celebrate a goal against their former club and look sulky instead. For goodness’ sake, it’s football, not real life. OK, I’ll make an honourable exception and allow one of these daft mimes to make it through my fortified gate of disapproval, as Hull’s re-enactment of their previous half-time bollocking against Manchester City was satirically witty and clever.

As full time approaches, players of the leading team will be encouraged by their manager to ‘run down time’ by taking the ball (via ‘the channels’) to one of the corner flags and standing there until someone kicks them. Failure to do this is ‘naïve’. And as the desperate minutes tick by, the required stance for worried fans is to clasp their hands together behind their heads to support their fretful visages.

If it’s a final we’re watching, the obligatory mode of celebration for teams who have won any competition, however pointless (Johnstone’s Paint Trophy, anyone?) is to squat behind a strip of sponsors-branded plywood and bounce up and down on their haunches. In the event of failure, fans must be shown staring into space, hands now positioned on top of their heads, presumably to stop them falling off. After a particularly crucial match, maybe involving relegation, skinheads, very large women and very small children are permitted to cry.

As you can imagine, my front room at Match Of The Day time is about as noisy as being at the match yourself, with quite as much atmosphere. Luckily my foul-mouthed vitriol and I escape ejection from the ground by virtue of being on home territory (first floor). I’ve nothing against the passage of time, and indeed offer it every encouragement. But I started watching football in the days of Hurst, Moore and Peters – come to think of it, in the presence of Hurst, Moore and Peters – and loved everything about it. Now it’s almost pure hatred. Ah well. See you next Saturday.

It’s not a good sign in a relationship when a row can be sparked off by the clock above the North Stand at Field Mill. When I say ‘relationship’ I don’t actually mean the full-on, heavy-duty thing. No, we’d been through the whole Relationship Cycle and were now in the winding-down phase, the other side of the emotional hill. We’d Got Together, we’d Been A Couple, had Split Up, Got Over It and were now Really Good Friends. The visit to Mansfield Town’s home match against Barnet was a symbol of our new-found maturity, a token of adulthood – the expedition mimicking the kind of things People Still In Relationships do, things like getting involved in some of your partner’s favourite activities.

It’s not a good sign in a relationship when a row can be sparked off by the clock above the North Stand at Field Mill. When I say ‘relationship’ I don’t actually mean the full-on, heavy-duty thing. No, we’d been through the whole Relationship Cycle and were now in the winding-down phase, the other side of the emotional hill. We’d Got Together, we’d Been A Couple, had Split Up, Got Over It and were now Really Good Friends. The visit to Mansfield Town’s home match against Barnet was a symbol of our new-found maturity, a token of adulthood – the expedition mimicking the kind of things People Still In Relationships do, things like getting involved in some of your partner’s favourite activities.

I’ll call the other character ‘the Ex’. Not that I like to define someone’s existence purely in terms of the role they used to occupy in relation to me. But it’s marginally better than ‘The Artist Formerly Known As My Girlfriend’, shorter too – and after all she never possessed the brand-changing clout of Prince. Then of course there’s data protection to consider. So I’ll go with ‘the Ex’.

Things started promisingly when, in the pre-match warm-up, she expressed admiration for striker Lee Peacock’s legs. I wondered briefly whether, at another time, I might have considered my own legs to be in competition with Peacock’s, but Iet that thought drop where I had picked it up.

The North Stand in those days was crowned by a clock which, sadly, was its most impressive feature. Ostensibly a timekeeper, the clock was in reality an advertising vehicle promoting the merits of John Sankey, self-styled as ‘Mansfield’s leading estate agent’. For that small subset of the Stags fanbase with a love of words and language it was a source of pride and wonder. Not because of any beauty in its design or precision in its measurement of the hours, but for the slogan that adorned its edges. This alone conferred a sense of character and uniqueness on the stadium. Boldly justifying the business’ pre-eminence was the intriguing claim: More people use Sankey than for any other reason.

I marvelled at the idea that some copywriter might actually have been paid to coin this phrase – doubtless also trying to dignify it with the term ‘strapline’. More likely, though, it was the product of some impromptu across-the-desks brainstorming session at Sankey Towers, in response to a tight deadline and non-existent budget. Some youth might have shouted “What about this?” and reeled it off in a rare moment of inspiration. And someone else would have punched the air and whooped “Yes! Brilliant!” Or, more likely, muttered “Yeah, that’ll do”. Over the years I had many opportunities to stare at and ponder this gem of tortured reasoning, both before and during games when often, for various reasons, I was praying for the final whistle. The clock even appeared on Fantasy Football League on television, when David Baddiel allowed himself a considered “hmmmm” and several seconds of silence, before delivering the verdict: “that’s deep”. On the face of it perfectly plausible, the boast isn’t so much profound as literally meaningless. Or is it?

During a particularly tedious passage of play, when Lee Peacock’s legs, for all their charm, weren’t doing the job they were being paid to do, I pointed to the clock, and asked the Ex to consider its sheer existential daftness. More people use Sankey than for any other reason, my arse. She gazed at it for a couple of minutes, as if divining the very essence of time itself in tandem with the meaning of the catchphrase, before coming back with “what d’you mean?”

One detail I haven’t already revealed to the court is that the Ex was a linguistics student. Correction, your honour, a postgraduate linguistics student – a status that had unaccountably always put me on the back foot in the whole arena of verbal communication. In fact, any kind of communication.

I smiled a kind of ‘are you joking?’ smile and tried again. But no, apparently it did mean something. Cheerfully embarking down the route of logic, I proposed that you can’t talk about ‘any other reason’ without giving a reason in the first place. ‘Other’ implies some kind of existing reason, one that’s already been stated. So it might work if it read: ‘More people use Sankey because they’re shit-hot than for any other reason’. That would make logical (if not commercial) sense. Or substitute ‘shit-hot’ with ‘local’, ‘dirt cheap’, ‘long-established’ – you get my drift. Don’t you?

No. The thing is, I learned, that more people use Sankey because more people already use it. That’s the reason. The sentence contains within it its own consequence; it possesses an ingenious circular logic. The reason is there, implied mind you, but present nevertheless, and I merely needed to alter my angle of perception to grasp it too. I could just about see this argument, but only through a thick, soggy, grey sheet of conceptual gauze. I could even understand that the advertising concept might be some kind of ‘follow-the-herd’ viral marketing approach, where customers would base their choice solely on how countless others already rated John bloody Sankey. But then shouldn’t it be: ‘More people use Sankey because a lot of different people already use it than for any other reason’?

Inevitably, the conversation descended from here into the pit we thought we had long since escaped. Sentences beginning with “you always”, “yes, but you never”, and “this is just”. Statements ending with “if you say so” and “whatever you like”. Declarations simultaneously beginning and ending with “I give up”. Eventually I resorted to intellectual abuse and suggested that the Ex’s rationale would be described by her own linguistics professor, in the specialist terminology of that discipline, as ‘complete bollocks’. We watched the rest of the match in uncomfortable silence. I think it was 1-0, but I can’t remember who won. Not goodwill and tolerance, anyway.

I still don’t know if I’m right, or indeed if there is any ‘right’. I feel somehow that there must be, but have never received the judge’s ruling. I suppose I walked free on a technicality. I have tried this out on other people since the event, telling the story as impartially as I could, but they generally didn’t want to get involved – either in the logic bit, or the right-and-wrong bit. Probably felt that taking sides would somehow compromise their professional standing or credit rating.

Over the years I’ve nurtured a growing sense of resentment against Sankey for the havoc wreaked by his few ill-chosen words. But still he seems to be thriving, oblivious to the damage he inflicted on our fragile accord with his loathsome timepiece.

The clock is long gone; it disappeared when the North Stand was demolished and rebuilt, giving new hope to other ex-couples as they try to forge their own embryonic friendships at Field Mill.

I’ve haven’t had any contact with the Ex for over seven years. I left a voicemail message in summer 2005, but received no reply. And I didn’t even mention Sankey. Ah well. I can only conclude that more people don’t return calls than for any other reason.

I approach the top of the escalator and head for the ticket office to renew my Oyster card for another week. It’s been a bad day, and of course the ticket office is closed. Inevitably for half an hour, just long enough to make it not worth while waiting. So that’s another 15 minutes queuing tomorrow. I pollute the north London air with loud and vitriolic curses about London Underground Ltd and its staff. Suddenly, surprisingly, the Station Manager turns helpful. He takes me furtively into the ticket office, where the clerk is taking a break behind a pulled-down screen. It’s like being invited into the staff room at school, or backstage at a concert. An inner sanctum of peace, taking me back to the 50s with its wooden drawers, ancient filing trays, words like ‘dockets’ and ‘requisition forms’ all around. They serve me in private and swear me to secrecy. As if I’d tell.

I approach the top of the escalator and head for the ticket office to renew my Oyster card for another week. It’s been a bad day, and of course the ticket office is closed. Inevitably for half an hour, just long enough to make it not worth while waiting. So that’s another 15 minutes queuing tomorrow. I pollute the north London air with loud and vitriolic curses about London Underground Ltd and its staff. Suddenly, surprisingly, the Station Manager turns helpful. He takes me furtively into the ticket office, where the clerk is taking a break behind a pulled-down screen. It’s like being invited into the staff room at school, or backstage at a concert. An inner sanctum of peace, taking me back to the 50s with its wooden drawers, ancient filing trays, words like ‘dockets’ and ‘requisition forms’ all around. They serve me in private and swear me to secrecy. As if I’d tell.

Your favourite music often fixes special occasions in the memory, and in time the two merge inseparably. When you especially love the music, and it’s connected to a really big event, you can never again think of one without the other. That’s how it is for me, anyway.

Your favourite music often fixes special occasions in the memory, and in time the two merge inseparably. When you especially love the music, and it’s connected to a really big event, you can never again think of one without the other. That’s how it is for me, anyway.

I saw Dolly Mixture many times in London in the early 1980s and bought the few records they released. As so often, I came across them supporting another much-loved band. I’d turned up the Venue in Victoria, London in January 1982, to see Orange Juice. Edwyn Collins was in a foul mood that night, but Dolly Mixture had already lit up the evening with an astonishing set, leaving me on a high that not even the grumpy Postcard janglers could bring down.

I was the token pop freak in the music faculty at King’s College, London University. By day learning about the avant-garde styles of Berio, Boulez and Stockhausen and equally abstruse medieval techniques of Dufay and Dunstable, after hours I was moonlighting as a part-time punk, taking in as much of the rich new music scene as I could. There was plenty, and I was a regular at places like the ICA, the Lyceum and Marquee, enjoying this novel vein of melodic, guitar-fuelled pop which had supplanted the increasingly dead-end punk and its angsty post-punk offspring.

The Venue was my place of choice, partly for the seemingly endless programme of amazing music I saw there, but mainly for its rather seedy ambience. Beyond the entrance hall there was a long, dark passage-way to the auditorium, exciting to walk down as you felt the growing anticipation of seeing a band you loved, and then this wonderful room – a big stage, a bowl-shaped dance floor, and at a higher level behind it tables and chairs.

Dolly Mixture were a fascinating thing. On the face of it a straightforward all-female power-pop trio of guitar, bass and drums, they had a repertoire of simply stunning songs. Reeling them out one after the other I’d alternately long for their sets not to end or wish for them to stop immediately, as they surely couldn’t get any better. The songs positively glistened. All three musicians sang, and their voices, in different ways, were sublime. Fresh, bright melodies, luscious chord sequences, tight, vivid harmonies, and a punky approach to belting out the music. Their ‘look’ was a combination of old-fashioned dresses apparently borrowed from a 1950s church fete and Doc Marten boots, the contrast neatly mirroring the music. Engaging and loveable on stage, they inspired a passionate live following including, sometimes, a devoted skinhead contingent.

The last time I saw them as a London resident was back at the Venue, on 30 March 1982. I was leaving for good the next day, and I’d taken along a friend I worked with in the University bar, to catch them just once more and hook him in as a fan. The band, this time headlining, were better even than two months earlier. Their set was like a greatest must-be-hits package – Never Let It Go, Angel Treads, Never Mind Sundays, a glorious cover of Love Affair’s Rainbow Valley, many many more. It was musical bliss to be there that night.

Between songs I turned to my friend and asked “What do you think, then?” Gazing wistfully at the bass player he simply replied “She is. Absolutely. Gorgeous”. Yes, and the music was pretty damn good as well.

Later that night I lay on the floor in Simon’s room in his hall of residence, the window open to the warm spring air, and we listened to The Teardrop Explodes’ Kilimanjaro and talked till we fell asleep. Down the road was the three-ton lorry I would drive to Stockton-On-Tees the next day to start a new job which would change the rest of my life. The exquisite sense of expectancy, knowing that something special would happen the next time the sun rose, is a feeling I can recall at the flick of a time-switch in my mind. And the music that accompanies it is Dolly Mixture’s.

They never made the step up to the next level of popularity and success, except in a brief cameo role as Captain Sensible’s backing singers. Maybe it was bad luck, maybe lack of management clout. Perhaps it was their laudable refusal, in a still male-run business, to allow blokes to write their songs and play their instruments – which, incredibly, was demanded of them as the price of a decent recording budget and a bigger label to release their records.

I often returned to London for odd days and weekends, and would always seek out Dolly Mixture until they split up in 1984. In the 17 years before moving back permanently I made do with the records and the memories. Everything And More would have worn out if I hadn’t copied it onto cassette. The Demonstration Tapes double album the band released under their own steam showcased their songs perfectly, unspoiled by being tarted up by any big-name producer. They sounded exactly as I remembered them live.